They’re the words every instrument pilot dreads: “Cleared for the back-course approach.”

Yes, I know. There aren’t many of those procedures in use, and even when they are available, controllers are more likely to issue a circle-to-land clearance on the standard localizer/ILS.

Still, they’re a nuisance we’re sometimes forced to deal with. It’s so simple and logical to fly into the needle that pilots are nonplused at the thought of flying the needle “backwards.” In every other variety of instrument procedure, the pilot corrects into a diverging needle — needle left, correct left; needle right, correct right. Even on a non-directional beacon (NDB) approach (assuming the station is still in front of the aircraft), the pilot flies the head of the needle and corrects left for left and vice versa.

Pound that message into a pilot’s head a few thousand times during private, commercial, and instrument training and then see what happens when sensing becomes reversed.

Back-course localizer approaches subject a pilot to reverse needle indications on the OBS. You fly right to correct left and versa vice — totally counterintuitive to pilots who’ve been taught that you always fly into the needle.

Fortunately for those pilots who use the airspace regularly for business and pleasure, back-course approaches are rare, and that’s understandable. Whenever possible (barring complaints from the neighbors under the proposed approach path), airports lay out their runways into the wind. Geographic and political features sometimes make that impractical, but most of the time, runways are oriented to allow pilots to benefit from some slight headwind on landing.

Similarly, the prevailing ILS is typically oriented to the longest runway. The implications for instrument students should be obvious. It’s almost impossible to practice back-course approaches because you’re most often flying directly into the flow of traffic coming off the most active runway.

How I learned the approach

For better or worse, I had a back-course approach in my backyard when I was working on my instrument rating in the ’70s. I learned to fly in the Los Angeles Basin, good news and bad news depending upon your point of view. Then, as now, LA was one of the world’s busiest areas for air traffic, especially general aviation.

At one time in those questionably halcyon days, the LA Basin was home to four of the 10 busiest airports in America: LAX, Van Nuys, Long Beach, and Torrance. The last three were predominately reserved for light aircraft, though Long Beach did have some airline operation. Collectively, there were something like 18 airports crammed into a fairly small area. In short, LA’s airspace was (and still is) very busy.

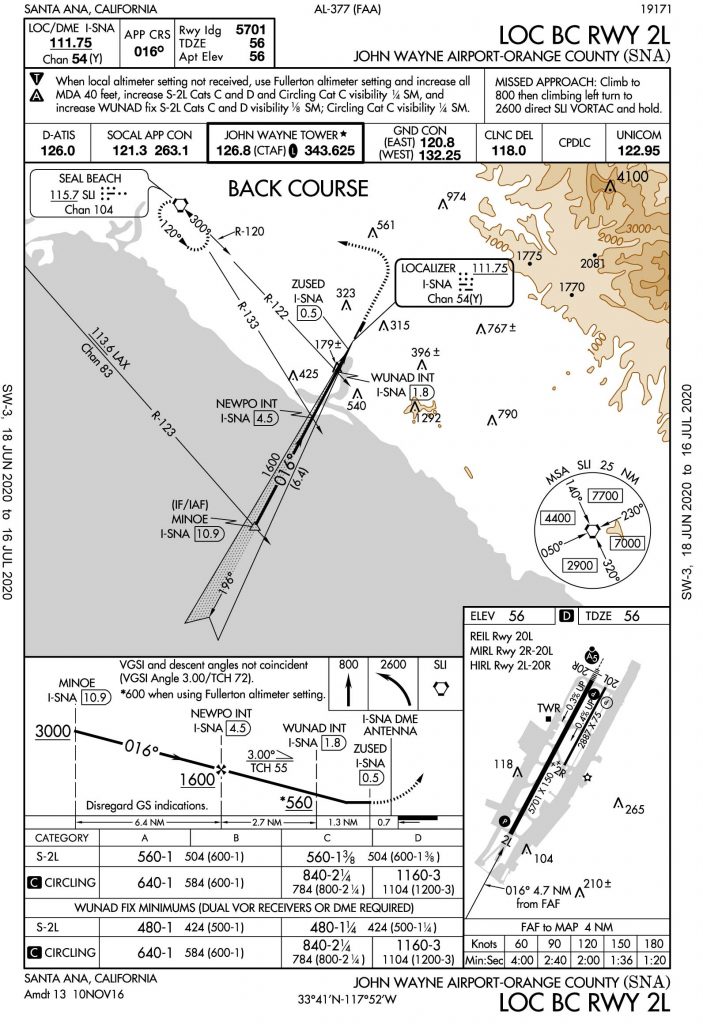

The good news was that with that many airports around, you could find practically any kind of approach you could imagine, and the John Wayne Airport, Orange County back-course was one of them. My instructor made it a point to insist one morning that we be in position to shoot the Runway 1 back-course to Santa Ana, California, at sunrise, the very moment the airport opened for business and a half hour before the parade of airline 737s began departing and arriving. Fortunately, there were no other idiots up that early, so we were able to get in two practice back-course efforts to missed approaches before the tower shooed away our little Skyhawk.

The better news is that it’s equally difficult for an examiner to gain access to a real, live back-course approach (unless they too are willing to conduct their examination at 6 a.m.), so most of the time, you shouldn’t have to worry about demonstrating your proficiency.

The rest of this article can be seen only by paid members who are logged in.Have a website login already? Log in and start reading now.

Never created a website login before? Find your Customer Number (it’s on your mailing label) and register here.

Still have questions? Contact us here.