By Joel Turpin, ATP/CFII/FAA Master Pilot

In 1961, veteran airline captain Ernest K. Gann published one of the most cherished books of all time for pilots. Fate is the Hunter explored how the most inconsequential detail of a flight, such as a change of airplanes just prior to departure or flying 50 feet above one’s assigned altitude, could have life or death consequences later. Although Ernest Gann cut the engines of life many years ago, the vagaries of the piloting profession he experienced in the late 1930’s through the 1950’s are timeless.

In over 58 years as a pilot, I have learned many lessons in the proverbial “School of Hard Knocks.” One of the most important lessons learned was that the one thing you don’t check on the exterior pre-flight inspection or cockpit setup, is the very thing that will be wrong.

For example, if you fail to check a certain circuit breaker, it is almost guaranteed that circuit breaker, out of a hundred others, will be the only one that is tripped! This truism was learned one fateful day when I was employed by Skyway Airlines as a 25-year-old Beech 18 captain.

The Little Things

On the hot summer morning of July 2, 1975, I was dispatched to fly Beech E18S, N3971, on a scheduled, round robin passenger flight. My route would take me from our home base at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, to Lake of the Ozarks, St. Louis, back to Lake of the Ozarks, and finally terminating at Fort Leonard Wood.

Skyway’s Beech 18’s were configured for commuter airline operations with seats in the cabin for nine passengers and a crew of two. However, in VFR weather, we often flew without the luxury of a copilot, especially if the manifest showed 10 passengers. In that case, the copilot would get bumped and his seat taken by some lucky passenger.

Upon reporting for duty that sultry summer morning, I was immediately told by our dispatcher that no copilots were available for my flight. This meant a single pilot operation for four legs and its attendant increase in workload for me, the captain. Taking this development in stride, I began planning for the day’s activities by checking the weather and filing a VFR flight plan for my itinerary. I then headed out onto the ramp and began a thorough pre-flight inspection of the venerable N3971.

One of the items to check was the elevator trim tabs, their actuator rods, and the nuts and bolts that connected the rods to their tabs. Since the Beech 18 is a tail wheel airplane, this required the pilot to bend over, lift up the elevator, and inspect the trim tab actuator rods exiting from the underside of the elevator. This I did, and found that the trim tab’s nuts and bolts were all there, as they had been on every check I had made for the past two years. However, I had missed a minor, but very significant detail that would almost cause the loss of the airplane later.

With my pre-flight activities complete, I departed Fort Leonard Wood for Lake of the Ozarks, arriving on schedule.

Once again, I did a pre-flight walk around inspection, found nothing amiss, and departed with ten passengers for St. Louis, arriving there about 15 minutes behind schedule. Being late, with a short turn-around time, meant I would have to hurry to depart on time for Lake of the Ozarks.

While my passengers were taking their seats in the cabin, I began my exterior pre-flight inspection. When I got to the tail section, I reached for the elevator to inspect the trim tab actuators, but hesitated. I thought to myself, “The trim tab nuts and bolts were all there on my last two inspections and have always been there for the past two years. What are the chances one of them could be missing now?” With that as justification, I neglected to lift the elevator and continued my way around the airplane. It would be an omission I would soon regret.

With all pre-flight check lists complete, I brought the two Pratt and Whitney R-985’s radial engines to life in a cloud of smoke and taxied for takeoff on Lambert Field’s Runway 12 Left. Upon arrival at the end of the runway, I was cleared for takeoff with instructions to turn left to a heading of 300 degrees.

What the Heck?

The takeoff was uneventful, and I turned onto my assigned heading while climbing to cruise altitude. With the harried ground activities behind me, I set climb power and started to relax. At that moment, a strange aerodynamic phenomenon occurred, and my routine flight quickly turned into terror!

Climbing 1,000 feet on my assigned heading, without warning, the airplane pitched over violently into an un-commanded dive. The pitch over was so abrupt that my heart skipped a beat. Instinctively I pulled back on the control wheel and wrestled the Beech 18 back into straight and level flight.

With adrenaline fueling my heartbeat into a flutter and my jaw agape, I steadied the pitch attitude and regained control. But before I could even begin to analyze what had happened, the nose pitched over even more violently than before, filling my very being with unmitigated terror!

Once again, I countered with a hefty pull on the control wheel and recovered into straight and level flight. At that point, N3971 settled down into its former self and motored on as if nothing had ever happened.

Peace Secured?

Of all the possible emergencies a pilot may encounter, there is nothing more terrifying than an in-flight control failure. Not being able to control pitch attitude, altitude, or direction of flight brings on a fear that is nothing less than primal. And even though my airplane was now behaving in a perfectly normal manner, the bolt of fear I had felt was still palpable. With both hands firmly gripping the control wheel, I continued on my way towards Lake of the Ozarks while climbing to 6,500 feet.

An hour later I was passing just north of our maintenance headquarters located on the Rolla National Airport, near Vichy, Missouri. I gave a call on the company radio to my friend and colleague Bob Rhodes, Skyway’s Chief Mechanic. I described to Bob what had happened with the caveat that when I landed at Lake of the Ozarks, I would not be flying N3971 again until the mystery was solved. Bob replied that he would round up some tools and another mechanic and drive over in a company truck and meet me there.

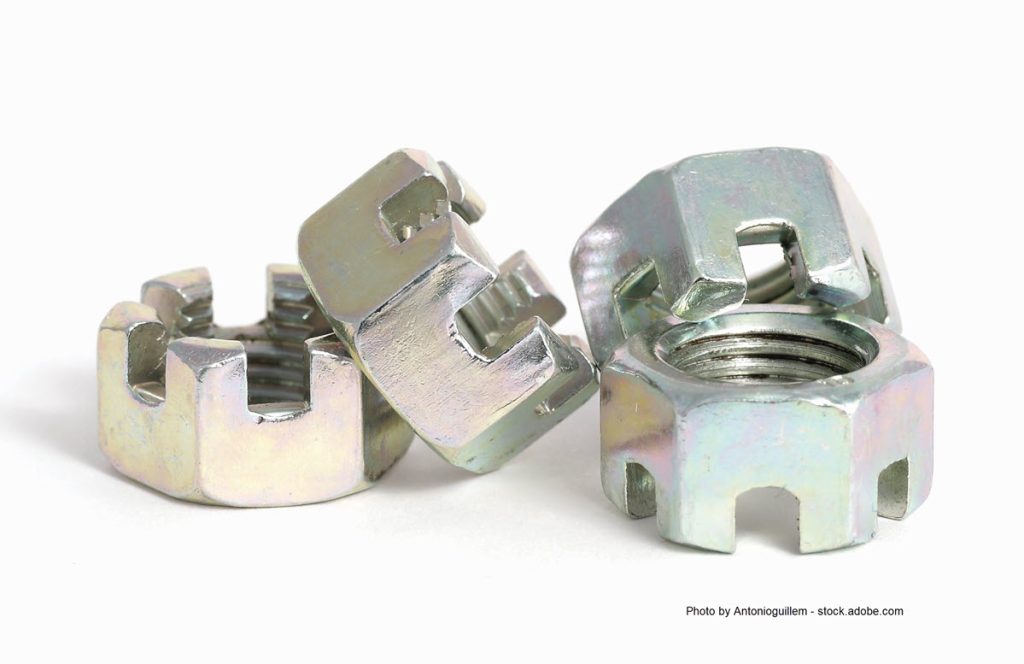

The Castellated Nut

The nut that holds the trim actuator rod to the trim tab is supposed to be held in place using a bolt with a hole in the end, a castellated nut, and a cotter pin. The cotter pin was supposed to be routed through the “castles” on the nut and bent at the end to secure it in place. While I saw there was a bolt in the trim tab control rod secured with a nut during my two pre-flight inspections, I failed to notice that the cotter pin was missing, and that a standard nut had been incorrectly installed in lieu of the castellated one.

As I cruised along, I tried to figure out what had caused the Beech 18 to try to self-destruct, but couldn’t come up with any logical answers. I was also feeling betrayed by an airplane I had not only come to trust, but had come to love. It was like an old and friendly family dog who suddenly bites its owner for no obvious reason.

Then my thoughts turned to the impending landing at Lake of the Ozarks. What would happen when I lowered the flaps and gear? What if the airplane pitched over on final approach? Was there anything I could do to prevent it from happening again? I didn’t know and had another 15 minutes to contemplate my fate.

Five miles out, I made contact with our agent at the uncontrolled Lee C. Fine Memorial Airport and found the active was Runway 21. I entered a left base, lowered the landing gear and set the flaps to the approach setting with no pitch problems. About 1 mile from the runway, with trembling hands, I lowered full flaps and set the prop controls to high rpm, with no ill effect.

But just as I crossed the runway threshold at 50 feet, the genie leaped from its bottle and the nose once again pitched over violently. Instinctively, I yanked the control wheel back and rammed both throttles forward in an attempt to use the engines to help raise the nose. By the grace of God, I got the nose up to a level attitude just as the main gear slammed onto the concrete. The Beech 18 reacted angrily by bouncing 5 or 6 feet into the air. With the control wheel full aft, I yanked the throttles back to idle, and another rough landing ensued, but this time there was no bounce. The ordeal was finally over.

Parking on Skyway’s ramp, I shut down the engines and deplaned my passengers, who surely thought their pilot needed some remedial training on how to land an airplane. Embarrassed by the rough landing, I avoided eye contact with my passengers, but nevertheless, I could literally feel their scathing stares. For some reason, I could not bring myself to tell them there had been serious problems with the flight controls, and that their lives had been in grave danger.

The Final Word

While pondering the great aerodynamic mystery, Bob Rhodes and his helper pulled onto the ramp in their truck and parked next to my Beech 18. I walked over and greeted the two young mechanics, then described in gory detail the strange antics of the airplane that had struck such fear in my heart. Without speaking a word, Bob strolled over to the tail of N3971, lifted the elevator and pointed out the cause of my travails.

The nut and bolt that secured the control rod to the left elevator trim tab were both missing. With the bolt missing, the tab was free to move at the whims of the air flow over the top of the elevator. At certain angles of attack, the airflow created a low-pressure area above the trim tab that would pull the trim tab upward, forcing the elevator downward. That bolt had been in place for the past 2 years of checking it religiously. The one time I didn’t check, it wasn’t there, validating the title of this story that Fate… is still the hunter!