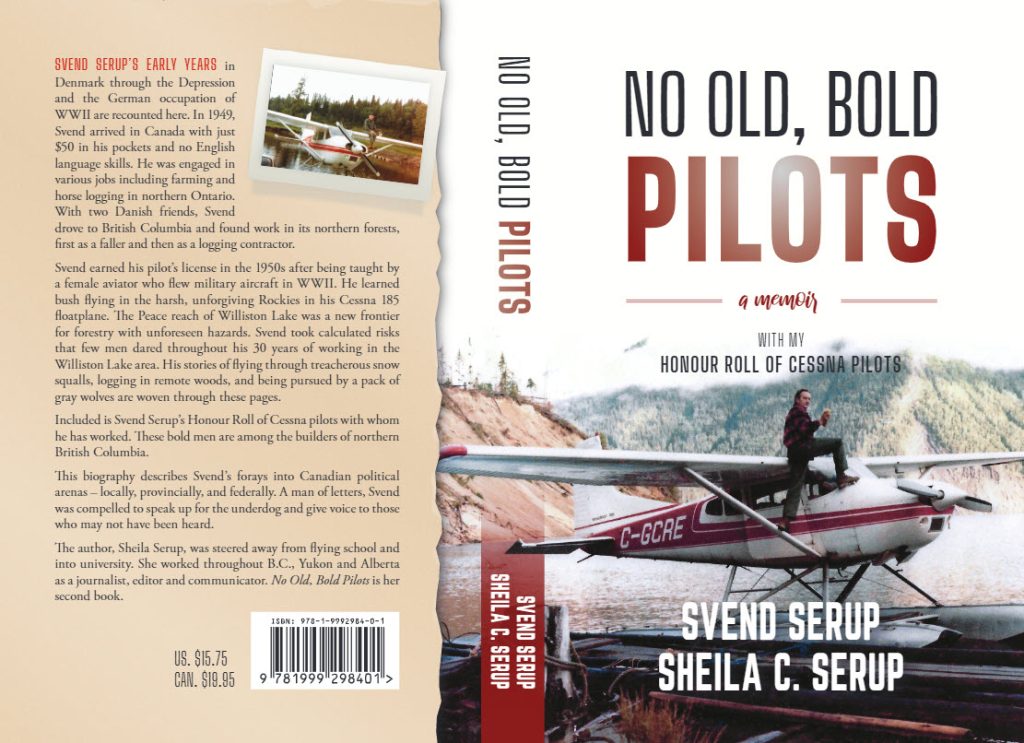

No Old, Bold Pilots, a Memoir with my Honour Roll of Cessna Pilots by Svend Serup and Sheila Serup (2nd Ed. 2021) \

That year in 1975, I seized the opportunity to buy my own plane. My previous flying experience had all been at the wheels of Cessna aircraft and I was confident that this backcountry workhorse would meet my challenging needs in the north. I had the opportunity to buy a new Cessna A185F on cap floats. This six-seater Skywagon had a 300-HP piston engine and its maximum take-off weight was 1519 kilograms. The four seats in the back could be easily removed to make room for equipment and supplies. I bought the plane for a total of $55,000 Canadian ($53,530 US)

In summer, it took one hour to fly to camp. I had to fly a route over the mountains which meant I had to fly higher than 6,000 feet. If there was a low overcast of clouds, I would have to follow the lake around Finlay Forks which made for a longer flight, around 20 extra minutes.

Flying in summer in a small plane can be a wonderful experience. I flew with equipment parts, people and groceries. I was often loaded to the maximum weight allowable, and sometimes I had difficulty getting airborne.

The floats would leak a little. With a full load, I had to pump all the float compartments to be sure they were empty. Sometimes on a clear summer day, after taking off from Tabor Lake or the Nechako River in Prince George, I would bring the plane up to 8,000 or 10,000 feet and find the air perfectly still.

After flying all the way over the mountains, I would have to come down in a long descent to camp. Other times, I might dodge thunderstorms or be required to fly under low clouds. I flew by visual flight rules which stipulated that my plane had to be 500 feet away from any cloud. Having an instrument endorsement would not have been much help when flying into camp with no radio contact from an elevation of about 6,000 feet or lower.

The Peace Arm of Williston Lake was known by pilots to be a rough area to be flying in. This narrow strip of lake, between Finlay Forks and the Bennett Dam, 115 kilometres long (72 mi.), is bordered by steep mountains on both sides. Strong winds would funnel in through this trench at high speeds. On a calm day, the surface of the water can be changed into raging whitecaps within minutes. Winds in excess of 80 kilometres an hour (50 mph) are not unusual. In some areas of the lake where it is eight to 12 kilometres wide (5-7.5 mi), there are clashing crosswinds. Shifting sand banks frequently cause landslides which can create tidal waves of up to three metres (9 feet) high.

Driftwood on Williston Lake could be a real problem. One time at our camp at Bernard Creek, our little bay was completely choked with driftwood. I was hoping the wind would shift and push it out. It didn’t happen. In the afternoon when I needed to fly out, I started up the engine and with it idling, I started with the pontoons to push this huge mat of driftwood out. Finally, in this manner, I reached the open water of the lake and was able to take off.

Being Battered by Turbulence

One Saturday in the late autumn of 1977, I found myself in a flight that should have taken 25 minutes but took over three hours. And when I finally brought my little Cessna 185 floatplane down onto Tabor Lake, I had never felt so harried as I did that afternoon.

Earlier, at 1:30 p.m., I stood in the little cove at Weasel Creek where our camp lay on Williston Lake in northern British Columbia. My day had already had its measure of problems with equipment, staff, and weather. That morning I had to cancel further road construction as the fall rains had not ceased. Logging was still in progress, but the logging truck had broken a walking beam and both the trucker and construction crew had gone out on the taxi boat earlier in the day. My trucker had promised to come back the next day with new parts so that the last few loads of spruce trees could be hauled to the lake and operations shut down for the season.

As I prepared my plane for the flight to Prince George, I felt a strange uneasiness. The weather was unsettled, and an active storm was moving in from the west. I had been calling on the radio for a weather report with no luck in reaching anyone. As I was calling, I could see the storm engulfing the lake about 16 kilometres (10 mi.) to the west. I quickly made my decision to get away before the storm arrived. My plan was to fly east along Clearwater Creek, then through one of the mountain passes southward to Mackenzie. From here, the vast central B.C. plateau would give me room to fly under or around storms for the last 160 kilometres (100 mi.) to Prince George.

I felt a sense of impending doom. Even though I relied on my intuition, I was a businessman, and I was continually making decisions on the information I had at hand. I knew that when intuition and reason failed, there was still a third power and I confessed my uncertainty. I asked for God’s protection on the flight, and then I cast off from the dock. Shortly I was airborne over the main lake. Banking the plane to the east, I began flying along the Clearwater inlet. Here the turbulence rattled the plane. As I flew towards the end of the inlet where the creek emptied, the peaks in front of me were obscured by clouds, and snow was falling all along the high ground, closing the passes.

As I gained altitude, I tried the radio vainly. If I was going to commit to proceeding into one of these narrow passes in marginal conditions, it would be helpful to know the weather on the Mackenzie side of the mountains. If the fog and rain were extensive, I would become trapped. My chances for survival would be slim as I was not licensed nor equipped for instrument flying. I remembered that over a year ago, a single-engine Piper Comanche plane with four Americans bound for an Alaskan hunting trip had disappeared between Prince George and Prince Rupert. In this rugged terrain, it would not be easy to locate a downed aircraft.

At 4,500 feet, I could not reach Prince George on the radio. I knew I should be flying at 6,000 feet to gain radio contact in this area, but the overcast skies prevented me from soaring any higher. By turning a little, I could see the storm closing in behind me, and I quickly banked the plane into a tight 180 degree turn so I would not be cut off from the lake.

The turbulence was becoming uncomfortable. Just as I was over the creek, my eye caught something disturbing on the instrument panel. A bright red light was flashing on the right-hand side. Above it were the words: ‘High Voltage.’

I had purchased the Cessna brand new two years ago and never had any problems. In fact, I had not studied in detail its parts and equipment. Now I was wishing I had. Could ‘high voltage’ mean just that? That the voltage was too high and consequently the instruments and radios might be damaged? As a precaution, I shut off both of my navigation and communications radios. They were useless anyway in this location with the Rocky Mountains blocking signals from all directions.

Now I focused on finding an emergency landing area. Every good bush pilot constantly stakes out such places where he might conceivably land his plane and be able to walk away from the landing. In this particular area, a long straight stretch of creek would be best. In late fall, the water level was low and gravel bars were exposed. If I landed there, I could avoid the trees on the side where the water was deepest, but my floats would be ripped open on the gravel on the shallow side of the stream.

But the engine purred smoothly. I knew enough about airplane engines to know that the two magnetos which delivered the sparks to the plugs worked independently of the electrical system, and therefore the engine would not be affected by a malfunction elsewhere.

I expected to set down in the little cove I had left 20 minutes ago. And I promised myself I would not attempt to leave until I had gotten through on the two-way radio and had information on the weather, as well as advice on the red warning light. I could see that the edge of the storm now touched the cove and my camp, but I figured I could get into the cove before the waves built up to impossible conditions.

Ahead on the Clearwater Inlet, I could see signs of the wind gusts racing across the water’s surface. From the air, I could see the cove and I instantly changed my mind about landing. The water in front of our camp was a boiling black mass. The wind was blowing spray from the lake into the air. I quickly banked my plane to the right and I felt the power of the wind when a turbulent gust hit the plane and the right wing dropped. I quickly stabilized the plane by correcting the ailerons and rudder. The plane righted itself. I decided to keep the air speed at 120 miles per hour which was double that of my stalling speed. This helped me to control the plane.

I could still feel the grip of the storm which at times shook the plane as a dog shakes a rag. I made a wide turn across the lake towards the sheer cliffs on the north shore but before I reached these, I had managed to come around and was heading east away from the storm. I instinctively knew that to continue westward, the shortest route home, within the black, turbulent void would be folly. There were forces that would tear apart a plane or dash it into the lake or cliffs. I found that my feet would not rest steadily on the foot pedals, the rudders. Instead they shook violently. I kicked my feet and stretched them, and soon the muscles calmed down. While I was doing this, I was rapidly thinking what to do next.

I decided to continue east along the lake towards the Pine Pass where I might be able to follow the highway through the mountains. After 10 minutes of flying, I switched on my radio. Here only low hills separated me from the prairies of northern B.C. I soon heard the Fort St. John radio tower loud and clear as the controllers were advising a pilot who was landing at Fort St. John. The weather in Prince George was good. Nothing was known about Mackenzie as no one was on duty there on the weekends. There were no reports of pilots having gone through the Pine Pass.

I was now at the far east end of the lake. Beneath me sprawled the huge W.A.C. Bennett dam and power station which produced half of B.C.’s power supply. Further ahead, I could see work in progress on a new dam that was being built below. I now turned southeast over unfamiliar country, bypassing the town of Hudson’s Hope. Studying my map, I was able to find my direction by the position of two small lakes. Bursting through a snow shower, I soon had the Hart Highway within sight, and I turned to follow it. But as I came up against the ramparts of the Rockies, I could see that the peaks were still obscured by clouds and snow was falling. I pressed on as far as where the highway makes a sharp-S turn along the course of the Pine River. Here I encountered a heavy snow shower with scant visibility.

I could attempt to follow the road at low level, but now I had a pilot’s report from Mackenzie. The weather there was within the limits of visual flight rules. Forty miles of flying through the mountains in snow showers was not a pleasant thought. Now I was being battered again by turbulence. On my right, I could see the valley and the Pine Pass over the Rockies which I needed to cross to reach Mackenzie. The narrowness of the valley was both impressive and chilling. How would I make a 180 degree turn if I had to turn back?

Caution is the virtue which allows pilots to grow old. I quickly banked my plane steeply in a tight turn to retrace my route back to Hudson’s Hope on the Peace River. I now advised Fort St. John’s control tower that I was turning back and would land on the river by Hudson’s Hope to wait for the weather to improve. This was not a comforting plan. Although snow showers were expected to die down by the evening, it was late Fall and the days became darker earlier. It was likely I would not get home until the next day.

As I neared Hudson’s Hope, I kept looking down the lake towards the west. I saw a cloud formation reaching up to 10,000 feet but this was over the mountains to the north of the lake. I was soon over the river cataracts below the dam. From here, it seemed unmistakably clear that the storm had moved on, leaving good visibility along the lake. I called the Fort St. John’s radio tower that I would now attempt to reach Mackenzie by flying along the lake. Twenty minutes later, I passed my logging camp which I had left two hours ago. And in fifteen minutes I had cleared the narrow Peace arm at Finley Forks and the broad reach of the Parsnip lay before me.

After flying the 88 kilometres along the Parsnip arm, I landed at Morfee Lake at Mackenzie. Here I fueled up the plane and looked around for a pilot to help me with the ‘High Voltage’ red warning light on the dash. Both of Northern Thunderbird Air’s Beaver and Otter floatplanes were gone on a mission. There were no other pilots in sight. But why worry? The engine had worked fine, and it restarted without a hitch for an uneventful flight over the remaining 160 kilometres (100 mi.) to Prince George. I had made it home at 5:30 p.m., just in time to attend dinner.

No Old, Bold Pilots, co-written by Svend Serup and Sheila Serup, is a biography of bush pilot, builder and community leader Svend Serup. Included is Svend Serup’s Honour Roll of Cessna pilots who are among the builders of northern B.C. To purchase, please contact the author at sheila.serup@gmail.com