Entry-level trainer

Don Hennesey could easily have afforded something faster, larger, and more ostentatious. He was a successful real estate broker back in the day when real estate could actually be profitable.

Don had purchased his one and only airplane, a Cessna 140, in the late 1980s, and he told me he planned to die with it (no, not in it). He loved the airplane, felt it was “about as fast as his brain,” and didn’t aspire to anything faster, larger, or more modern.

Don accumulated some 700 hours in that little airplane in just over seven years, not bad for a weekend pilot who rarely flew farther than 100 miles at a time. I used to fly with him on some of his short trips around Southern California, and it was readily apparent he was in love with his little taildragger.

I was flying an old Mooney at the time, but I understood the attraction of a late 1940s-vintage two-seat taildragger. After all, I spent my first 30 hours of flying (all of it unloggable as I was underage) in a modified J-3 Cub in Anchorage, Alaska, then earned my certificate and survived 500 hours in a 1946 Globe Swift back in the 1960s, a puddle-jumper in its own right (though a nice handling one).

I may have had a slight advantage over the majority of the pilot population in that I never set foot (or butt) in a Cessna 150 until well after I was licensed.

For that reason, I had no preconceptions about the advantages of a nosewheel over a tailwheel.

In fact, I thought it was the other way around. In Alaska (and everywhere else), tailwheels have the advantage on unimproved runways, regardless of whether they are legitimate airports.

Simple efficiency

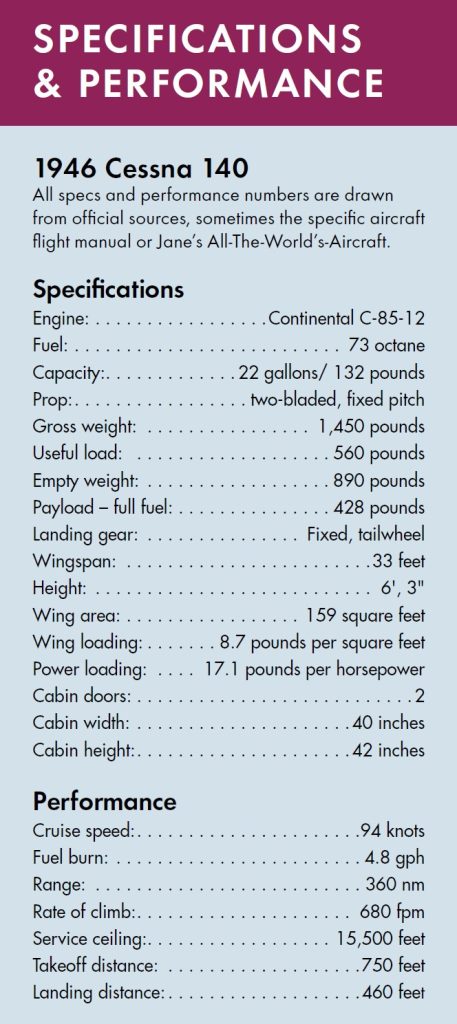

The Cessna 120/140 was something of a mini bird in the Cessna line, a machine designed for pilot training and the epitome of low-cost flying. With its hyper-economical 85-hp Continental engine (90 hp on the later models), the type was fairly efficient, despite the fact that fuel costs were hardly a factor in those days at about $.35 per gallon.

The 120 was the first iteration of the model, introduced in 1946 and produced through 1949, a super-simple machine with no flaps, no aft side window and (usually) no electrical system. The lack of electrical power obviously limited the 120 to day/VFR operation since, by definition, lights required an electrical system of some kind. The 140 was the more capable step-up airplane, though it shared the same fuselage and wing, and a pilot could start it unassisted without tempting fate or getting caught in a rainstorm.

Both models were intended to address the post-war aviation boom that wasn’t. Despite a low initial price of $3,495, most of the thousands of pilots returning from war didn’t have that kind of money, and many of those who did had memories of friends who didn’t return and, accordingly, they were no longer interested in flying.

The initial, entry-level Cessna featured an all-fabric covering until 1949 when the 140 converted to an aluminum fuselage and control surfaces with fabric wings. The improved 140A was the last of the type, built in 1950, offering a single wing strut on each side to replace the earlier V-struts, plus the option of a controllable pitch prop.

In total, something like 7,700 of the little devils were produced before Cessna shut down production of its post-war two-seater. The company began building the modern model 150 in 1959, a design that carried on with many of the 140’s components and concepts.

What didn’t translate was the tail wheel. By some estimates, that was unfortunate. Cessna was eager to move into the modern age, and the competition, primarily Piper and Beech, had transitioned to more modern nosewheel designs, which were notably easier to fly, even if they were heavier and more complex in construction.

Don Hennesey told me he’d flown a 150 before buying his 140, and he didn’t feel the newer airplane was as much fun to fly. Certainly, it wasn’t as much of a challenge, and therein lay the rub. Don was one of those guys who liked to test himself against the sky, even if the tests weren’t tough. If there was a crosswind blowing at Long Beach, Don would be out testing his ability. In 10 years of flying with him, I never found him lacking, and he never bent his airplane.

Fact is, many pilots enjoy the challenge of confronting and defeating new, more demanding conditions, despite (or perhaps because of) the fact they’ve never been tested so rigorously before.

Don passed away a few years ago, but his airplane lived on for several more years. I didn’t follow its chain of ownership, but I learned someone wiped it out in a nasty crosswind at McCarran Airport in Las Vegas. Don would have been sad to see his good friend crumpled in a pile beneath the neon casino signs.

Flying the 140

To be fair, the 140 isn’t that tough to fly during transitions to and from the earth. It is a very light machine, only 1,450 pounds gross, and almost by definition that means greater susceptibility to the vagaries of wind.

The NACA 2412 airfoil was nevertheless relatively forgiving of all but the most egregious transgressions. Stall speed was a low 39 knots, so you could approach at 48-50 knots without that verge-of-destruction feeling.

Stall characteristics with Cessna’s 33-foot-span, 159-square-foot wing were about as benign as they come. Frustrate a stall with full back yoke, and the airplane would usually buck and complain as the nose bobbed up and down, seeking flying speed and lift. Allow the ball to drift too far out of center, and the airplane could eventually get mad at you and drop a wing into a spin, but recovery demanded little more than forward yoke and opposite rudder. If you were simply awake, you could usually countermand a spin in one turn.

Performance

The diminutive Cessna could easily squat into places it couldn’t hope to leap back out of. Landing gear extenders were a popular option that increased the deck angle, improved the wheelbase, and made the airplane less likely to flip onto its nose under heavy braking.

Empty weight on the 140 was about 890 pounds, leaving a useful load of 560 pounds for a lightly equipped airplane. With a full 22 gallons of 73 octane fuel in the tanks (standard aviation fuel in 1946), this left a hefty 428 paying pounds for people and things in the cabin.

Considering that there were only two seats, that’s a substantial payload. It’s adequate for two big men plus toothbrushes or a typical couple and major luggage, assuming you could find a place to stow it.

When it was time to lift the weight into the sky, power loading was a controlling factor. With only 85 hp to boost 1,450 pounds, each of the Cessna’s horsepower had to elevate 17 pounds of airplane, so you couldn’t logically expect great enthusiasm during the ascent. Cessna bragged of 680 fpm climb, but most owners suggest that was optimistic. On a fairly standard day, Don’s airplane managed more like 500-550 fpm, and the alleged 15,500-foot service ceiling was little more than a dream.

Fortunately, there was usually no great rush to climb, and little reason to fly high. We were both too smart to take on a 6,000-plus foot density altitude at full gross. In one instance, we did launch from California’s Big Bear Airport (elevation 6,750 feet MSL), 60 miles east of Los Angeles in the San Bernardino Mountains, and we were grateful for a nice, flat lake that extended several miles out on the initial leg.

The 140 seemed happiest at relatively low altitudes — 2,000 to 6,000 feet AGL — and 75% power usually produced about 90 knots cruise, a speed that seemed quick enough considering that we were rarely in a hurry. The 140 was in every sense a fun machine, more sport plane than medium speed family transport. Pushed to max cruise, it burned about 4.5 gph, so its 22-gallon tank could provide an easy 3.5 hours’ endurance plus reserve. Pulled back to 55% power, it could linger aloft for more than four hours. This provided an easy range of 360 nm, depending upon who you believe.

Four hours in a 140 would have been quite enough for anyone, especially two men of modest beam. The cabin was a mere 40 inches across at the hips and not a lot taller, so long trips weren’t the 140’s strong suit. Don did fly his airplane to the Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta one year (about 600 nm each way) and he survived without any permanent spinal damage.

Don always talked about someday stepping up to the 90-hp engine, or even the STC’d Lycoming O-235 that pumped power to 108 hp, but it was never more than a dream. The stock engine seemed as bulletproof as they come. Don believed in running the Continental at full throttle most of the time, and he never had any problem with the durable C85-12F. Additional power probably would have offered a welcome improvement in climb, but I doubt there would have been much change to cruise speed.

What the 140 did best was take us to places I couldn’t even consider in my airplane. The book said landing distance was only about 300 feet if you were doing everything right, but takeoff demanded more like 500 feet, not that unusual for a low-powered two-seater. No big surprise that the owner flew the airplane better than I did, though I had the greater number of hours, and he was consistently able to sandwich into places I never would have attempted. He had the stock tires in place — none of those big, heavy, balloon bush tires for him — and he could consistently ground the airplane in what seemed a ridiculously short distance.

Some 140s in Alaska were actually fitted with floats and many were flown above skis. The ski undercarriage would have been fun, but I imagine floats would have relegated the airplane to low level, with precious little climb performance. Even so, a 65-hp Cub seemed to fly reasonably well on lightweight floats, so perhaps the 140 would have performed better than I expected.

Despite 65-plus years of attrition, there were enough Cessna 140s built that there is still a ready supply on the market. Most owners of Cessna’s first, real, entry-level, trainer are justifiably proud of their arrogant, little, fun, tailwheel machines.