By Jim Gibertoni and Joan Skilbred

On October 16, 1972, a Pan Alaska Airways, Ltd. flight from Anchorage to Juneau, Alaska, failed to make its destination and was never seen or heard from again. The plane N1812H, a twin-engine Cessna 310C, was owned by Pan Alaska Airways LLC. The pilot was Don Jonz from Fairbanks, and his passengers were United States Congressman and House of Representatives Majority Leader Thomas Hale Boggs of Louisiana, United States Congressman Nick Begich, and his administrative assistant Russel L. Brown both of Anchorage.

I have been a Search and Rescue (SAR) Pilot flying with the Civil Air Patrol here in Fairbanks, Alaska for almost a quarter of a century, logging more than 250 SAR missions to date. What I am about to share is a robust educated guess, based on the facts and my extensive experience in search and rescue.

It is important to note that Don Jonz submitted an article he wrote to Flying Magazine a few weeks prior to the fateful flight that was called “Ice Without Fear.” This article was published in the October 1972 edition of the magazine.

The NTSB Accident Report, in an unprecedented move, gave a full paragraph about the magazine article: “…it may be noted that previously he (Jonz) had authored several articles on the subject of flying under comparable adverse weather conditions. The article, among other things, advised pilots to be prepared for the situations that were likely to be encountered. For instance, he advocated that one always maintains: (1) a mental picture of the weather ahead, (2) a reserve of altitude, (3) extra fuel, and (4) an alternate course of action. He advised against flying into obviously bad situations, such as dark areas or precipitation when the outside temperature was in the critical icing range. To avoid icing he recommended that a doublecheck be made of the survival equipment aboard the aircraft and that the proper winter clothing be worn by all occupants of the aircraft.”(1)

Focusing on the NTSB report and the “Ice Without Fear” article, we can gain some new insights into what might have really happened. Clearly, in this case, there is no way any of us are going to have entire certainty as to the full details of what happened to N1812H, but we can follow the information trail and possibly locate the crash site.

Pre-Flight Facts

On October 15, 1972, the day prior to the loss of N1812H, Fairbanks pilot Don Jonz of Pan Alaska Airways, accepted a call requesting a flight to haul two United States Congressmen and an aide, from Anchorage to Juneau. Jonz was a commercial pilot and this was a real opportunity for his aviation business. If he accepted this request, it would certainly lead to further business opportunities for him. His plane had just come out of its annual inspection,(2) so it was up for the task.

The NTSB report states a witness said Jonz agreed to the request. He would also be flying the passengers without getting paid.(3) This means the flight from Anchorage to Juneau would be classified under part 91 of the FAA flight regulations.(4) He left Fairbanks International Airport at 5:58 pm for Anchorage, where he arrived at 7:40 pm and spent the night. That flight was uneventful.

The next morning at 6:56 am on October 16th, Jonz called Anchorage Flight Services (FSS) for a routine weather briefing. He requested to be briefed on Juneau, Sitka, Yakutat and Cordova weather. He stated, at that time, that he would be flying a Cessna 310 under Visual Flight Rules (VFR) to Juneau.(5) It is important to note that he did not ask for the weather briefing for Portage Pass at this time. However, he was told that Portage Pass was closed as part of that briefing.(6)

The National Weather Service’s surface weather chart that day, compiled by the Anchorage Office, showed “a warm front extending eastward from a point near Iliamna to a point about 50 miles south-southeast of Yakataga. A high-pressure system was entered off the coast of southeastern Alaska.”(7)

“The surface weather conditions as reported on the 0600 sequence reports were, in part, as follows for the stations indicated: (1) Cordova – ceiling measured 2,500 feet broken, 5,000 feet overcast, visibility 7 miles; (2) Yakutat – 300 feet scattered, ceiling measured 700 feet overcast , visibility 1 ½ miles in fog; (3) Juneau – ceiling indefinite 500 feet obscured, one-half mile in fog; and (4) Sitka – clear, visibility 12 miles.”(8)

The NTSB Report states on pages 4 and 5: “The later surface weather observations for the stations and times indicated were, in part, as follows: (1) Anchorage – 0900 – 4,000 feet scattered, ceiling estimated 6,000 feet broken, 8,000 feet overcast with 30 miles visibility, temperature 40° F., dew point 37° F., wind 300° at 8 knots; (2) Seward – 1000 – ceiling estimated 4,000 feet overcast, visibility 7 miles in very light drizzle, temperature 52° F., dew point 45° F., wind 200° at 28 knots with gusts to 33 knots, visibility 3 miles in northeast one-half; (3) Cordova – 1000 – ceiling measured 3,500 feet broken, 5,000 feet overcast with 7 miles visibility in light rain, temperature 47° F., wind 090° at 11 knots; (4) Yakutat – 1100 – 400 feet scattered, 2,000 feet scattered, ceiling estimated 4,800 feet broken, 20,000 feet overcast, visibility 20 miles, temperature 44° F., dew point 42° F., wind 060° at 6 knots; (5) Juneau – 1200 – ceiling estimated 600 feet overcast, visibility 4 miles in fog, temperature 41° F., dew point 38° F., wind calm; and (6) Juneau – 1300 – 700 feet scattered, ceiling estimated 20,000 feet overcast, visibility 12 miles, temperature 43° F., dew point 39° F., wind calm.” The NTSB report also contains further weather information at the end of the report as an attachment.

The only icing on the forecast was “moderate rime icing conditions forecast to exist in clouds from 6,000 to 15,000 feet over the Cook Inlet area.”(9)

The supplemental weather attachment in the NTSB report gives more details: “Cook Inlet, moderate to locally severe turbulence with strong winds, showers, and strong updrafts and downdrafts.”(10) There is also a footnote with the entry that states “An advisory concerning weather of such severity as to be potentially hazardous to all categories of aircraft.”

Most of that morning was routine, as far as getting ready for a flight goes. After receiving the weather briefing and filing his flight plan, Jonz fueled the plane up at 8:00 am. He had wingtip tanks for extended range which were topped off, giving him six hours’ worth of fuel for the trip.(11)

In the NTSB accident report, there is mention of a USAF helicopter that was enroute from Elmendorf to Seward. (12) The intended route was to fly along Turnagain Arm to Portage, then south along the railroad tracks to Seward. “The pilot stated he encountered moderate to severe turbulence at 500 feet m.s.l., headwinds of 55 knots, and broken to overcast cloud conditions 200 to 300 feet above him. He could see Portage, but the forward visibility was deteriorating. Due to the turbulence, he abandoned his attempt to reach Portage and took an alternate route via Sunrise and the highway south towards Seward.”

Around the time he got his passengers loaded, Jonz, no doubt, heard the radio transmission from a helicopter stating they were flying over Sunrise rather than Portage.

See the NTSB Accident Report in its entirety here: www.ntsb.gov/investigations/ AccidentReports/Reports/AAR7301.pdf

1 NTSB Accident Report page 8, paragraph 1

2 NTSB Accident Report page 6, paragraph 1

3 NTSB Accident Report page 6, paragraph 1

4 NTSB Accident Report page 6, paragraph 1

5 NTSB Accident Report page 2, paragraph 2

6 NTSB Accident Report page 2, paragraph 3

7 NTSB Accident Report page 4, paragraph 3

8 NTSB Accident Report page 4, paragraph 4

9 NTSB Accident Report page 5, paragraph 3

10 NTSB Accident Report attachment 2, page 2

11 NTSB Accident Report page 2, paragraph 4

12 NTSB Accident Report page 3, paragraph 4

13 NTSB Accident Report page 3, paragraph 1

14 NTSB Accident Report page 3, paragraph 2

15 NTSB Accident Report page 6, paragraph 4

16 U.S. Department of Defense website – www.defense.gov – “Sacred Search: Operation Colony Glacier”

In-Flight Logic

Don Jonz was a very experienced commercial pilot and, of course, would not fly into weather conditions that closed the pass. Nobody in their right mind was going to fly through Portage Pass on that day. However, the weather further down the Kenai Peninsula towards Seward was acceptable for VFR flying with temperatures in the 50’s.

If the flight plan was the Anchorage to Seward route, he could then fly over Middleton Island, which at that time was a federal facility with a lot of intelligence capabilities related to the cold war and the Vietnam War. Flying the congressional majority leader over that facility would be a big deal. Also, on that day he would have a strong tail wind after leaving Seward which would enable him to breeze right into Juneau by crossing the Gulf of Alaska.

The Seward route is also likely because he had a lot of extra fuel on board, almost twice what would have been needed for the Portage Pass route.

N1812H took off from the Anchorage International Airport at 8:55 am on the morning of October 16th. Air Traffic Control (ATC) recorded the last sighting of the plane being two miles out from the airport on a southeasterly heading at 2,000 feet, at 9:00 am.(13) This record is critical because it was part of the controller’s job to record that information using binoculars for every single flight. The entry by ATC is an official record of fact as to the last time N1812H was seen.

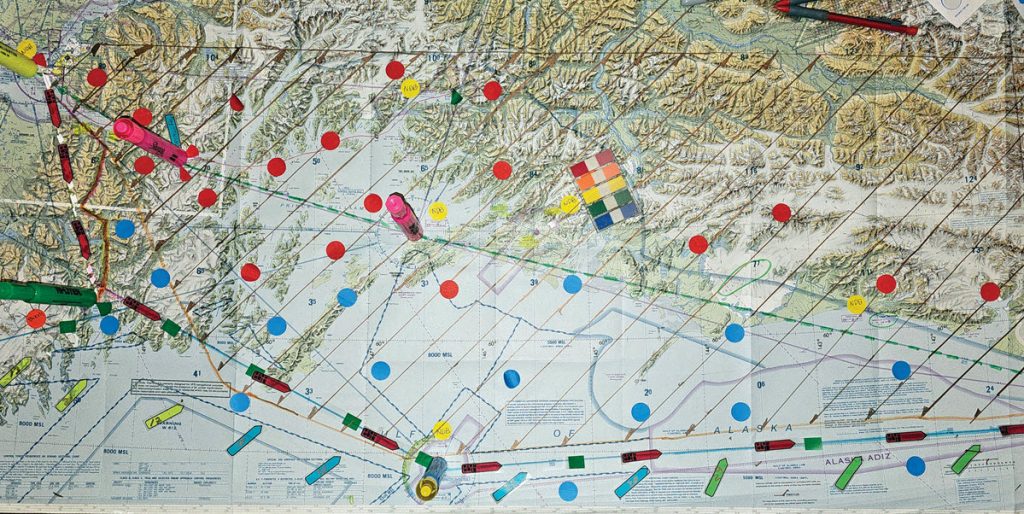

As an SAR mission pilot and team member, we look at that official record as a “stake in the ground.” It is the important last sighting of the aircraft that points the SAR operations in the right direction. We need to look very carefully at that entry. The direction southeasterly is a 130° heading which takes you to Sunrise. The Portage direction would have been a heading of 090°, a directional disparity of about 40°.

N1812H was last heard from 9 minutes later, when Jonz made routine radio contact with Anchorage Flight Services.(14) He stated there were four souls on board, they had six hours of fuel, and when asked if they had emergency gear on board, Jonz replied “affirmative.” The report states he filed the VFR flight plan as V-317 Airway through Portage Pass. At the time of that last radio communication, Jonz also received an updated weather report. That was the last time anyone heard from N1812H.

Final Hypothesis

The route through Seward and Middleton Island is located just outside of the designated search area. No search was ever conducted along that flight path. If we consider this alternate route, a new theory presents itself.

As they flew further south toward Seward, the weather began to improve, and they probably saw the grandeur of the Kenai Peninsula beneath them. Hale Boggs was from Louisiana and was an important politician on a national scale. He was here on a whirlwind campaign fundraising event to help Begich during the upcoming elections. This was a real opportunity for Begich and his aide Russel Brown to show Boggs the greatness of Alaska, which we purchased from Russia for two cents an acre.

The view along their route, looking southwest, included the Harding Ice Field, the largest ice field in the United States. It is comprised of more than 40 glaciers and encompasses an expanse of 700 square miles. It is also named after United States President Warren G. Harding.

Commercial pilots are trained not to be distracted in the cockpit. The problem is that opportunity was knocking. The pressure on Jonz to deviate from his intended route must have been intense. We have all felt that kind of pressure. What would you have done? Say “no way” to the U. S. House Majority Leader? It would be so easy to fly up either one of the Skilak Glacier fingers across the vast expanse of the ice field and down the Bear Glacier into Seward. That is the obvious and logical route that most pilots would take to see what is up there. He had plenty of fuel, the passengers were excited, so why not?

The next radio check would naturally occur when they began exiting the ice field via Bear Glacier, checking in with Seward then continuing the flight to Middleton Island. But that never happened. If the plane had gone down anywhere else along that Anchorage-Seward route, it would have been found by now. I strongly feel the most likely place it went down was somewhere on the Harding Ice Field or one of its associated glaciers.

I have considerable experience flying SAR missions over glaciers and ice fields. The Harding Ice Field has its own weather due to the massive amount of ice. Altimeters don’t always read accurately over these mammoth ice sheets and if the ceiling drops, you can suffer from spatial disorientation.

I cannot deduce what exactly happened to the plane, but it is obvious and logical that whatever happened was sudden and catastrophic because there was no call for help, and no other signal from the plane. If they had mechanical trouble, a call would have been made. If they were in severe icing, a call would have been made. If there was a disturbance or medical emergency inside the fuselage, a call would have been made.

What about an Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT)? At that time, they were not required by the FAA but Alaska law required them as of September 6, 1972.(15) That was one month prior to the fatal flight. In this case, it is hard to say whether that makes a difference or not. Back then, ELT’s worked, maybe, ½ of the time. If you go down in a glacier crevasse, an ELT won’t help you at all.

The Harding Ice Field has chaotic terrain concealed by a mantle of snow blowing and shifting across its surface. The glaciers are rippled with deep crevasses between steep mountain walls. The numerous terrain-related hazards, coupled with unpredictable weather changes, make for higher risks of sudden catastrophic events when flying over it.

Another scenario for consideration would be a bird strike. If they hit a bird while ascending the glacier, it could cause loss of control of the aircraft.

Thoughts For the Future

If N1812H is in the Harding Ice Field or one of its glaciers, entombed in tons of ice and snow, how would we find it? Amazingly enough, there are existing examples of recent recovery operations of long-lost aircraft and passengers from glacial environments.

On November 22, 1952, an Air Force C-124 crashed with 52 personnel on board and was never heard from again. It went down on the Colony Glacier near Palmer, Alaska and then, due to melting, reappeared in 2012. Since that date, most of the crash victims have been recovered and returned to their respective families.”(16 )

There have been a couple of planes recovered in the Swiss Alps that had been entombed in glaciers for many years. The melting back of these glaciers in recent years has exposed these old wrecks.

How would you recover N1812H in the Harding Ice Field? It could be done. In fact, it has already been done on another even bigger ice field in Greenland. A group of pilots and aviation enthusiasts recovered a World War II P-38 Lightning plane from the ice after many years of entombment.

The loss of N1812H and its passengers on October 16, 1972, has haunted us long enough. We need to stop chasing our tails by clinging to the ridiculous notion that they flew through Portage Pass on the V-317 Airway on the fateful day. It is time to give some respect to Don Jonz for the experienced pilot he was and to conduct a new search around the Harding Ice Field.

Obviously, we have the technology to do it. The logical question is, when are we going to attempt to use that technology to locate N1812H?

Jim Gibertoni came to Alaska in 1975 and became a journeyman plumber working on the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. He later started Aaron Plumbing & Heating which took him all over Alaska and as a result he became very familiar with flying small aircraft over a wide variety of conditions and terrain within Alaska. He joined the Civil Air Patrol in 2000 and has served as a mission pilot for the past 23 years, logging more than 250 SAR missions to date. He also has both commercial and instrument ratings. In 2003 he purchased his Cessna 206.

Joan Skilbred is a well-known local Fairbanks historian. She writes a weekly feature for the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, does radio shows and other historical lectures. She also owns and operates a small manufacturing company that caters to the winter bicycling market.