The quintessential Cessna 180

If you’re one of those pilots (like me) who read Arthur C. Clarke, Frederick Pohl, and Robert Heinlein and believe that people tend to look like their pets, it’s not much of a stretch to feel that some pilots come to resemble their airplanes.

Jack Pardo was like that. An Alaskan pilot who’d been kicking around the bush country of the far north for four decades, Jack had done it all — and it showed. The last time I saw him in 1976, he was a lean 70 years old (many of us thought he must have been born at age 70) with a lot of miles on him, a scruffy beard, and a disposition to match.

He had no use for pretension and the factors that nourished it — money, fame, and arrogance. He was a bush pilot to the core. He was good at what he did, simple, honest, unassuming, down home and out back.

Jack worked hard — when he worked — but he had no desire to be rich. He didn’t care much about money except to keep his airplane running and his kennel of huskies fed.

Jack’s airplane was a ratty looking but mechanically perfect Cessna 180 that traded wheels for skis or floats periodically depending on the mission and the season. When the airplane was new back in the late ‘50s it was probably blue and white, but the last time I saw it at the CAP squadron hangar on Merrill Field in Anchorage, Alaska, the paint had faded to an undistinguishable shade of gray.

Jack’s 180 had only one VHF radio of questionable parentage, an antique Bendix T12D ADF, essentially very little interior other than two seats in front, no rear seats most of the time, a handful of original instruments, a prop that had been dressed several times, and in summer a pair of huge balloon tires minus most of their tread.

Still, the engine started whenever it was asked and ran perfectly, the heater, artificial horizon, and compass worked, the flaps went up and down, and Jack felt that was all that really mattered. Jack flew the airplane like breathing; a pure reflex without thought. He knew exactly what the 180 could do, or perhaps more accurately, what he could do with it.

Jack and his Cessna 180 were well matched. Both were eccentric classics, old and more than a little tired, both had seen better days, but they were still competent and capable, always able to find another cheek to turn to the callous hand of time.

Jack ran out of cheeks a few years back and, as we all knew he would, he died in his sleep. No way that man could ever die in an airplane. He used to say he wanted to go at the controls of his C180, but we all knew better. Jack was too good. Those who knew him and his natural ability for bush flying figured he’d probably breathe his last in his sleeping bag under an alder somewhere out in the muskegs.

I never discovered the full story of Jack passing or what happened to his durable old 180, but I like to hope someone landed it in a meadow somewhere up in a remote corner of Alaska’s Brooks Range, 500 miles from anyplace with a name you might recognize, taxied it up under a stand of pine trees and left it there.

Some pilots have a reverence for certain airplanes that borders on the fanatical. So, depending on who you talk to, Cessna’s taildragging 180 may be that marquee’s most charismatic model, with a following that’s quietly devoted if not loudly outspoken.

Owners seem to consider the 180 Skywagon the quintessential Cessna and often wouldn’t even consider trading for any other airplane especially (horror of horrors) one that mounts the third wheel under the nose.

Fact is, by any measure, the 180 truly is one of the most talented Cessnas ever built. The Kansas company produced the 180 Skywagon from 1953 through 1981, and during that time, more than 6,500 examples trundled off the Wichita production line. The airplane’s conventional gear, good useful load, and easy, low-speed manners made it a consistently popular bushbird, but it also remains highly regarded as a conventional people mover, equally adept at transporting families, businessmen, or clients for the outback.

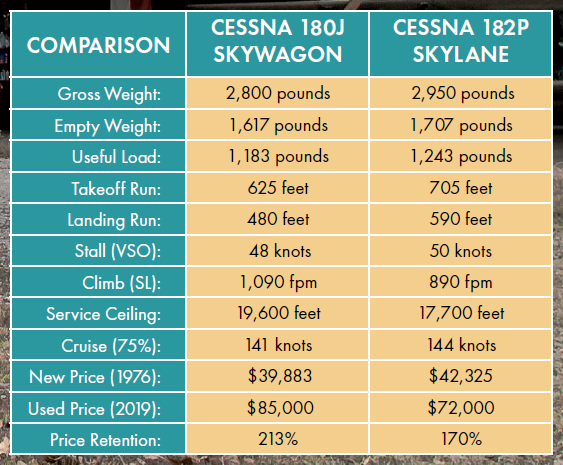

If you look strictly at the numbers, it’s apparent the 180 has some performance advantages over its tricycle brother the Skylane, but it’s not superior in all performance categories. Climb generally is a little quicker, service ceiling higher and takeoff/landing performance shorter, but cruise and useful load are better on the Skylane.

So what’s the big deal? The overriding attraction of the conventional gear Cessna 180 is exactly that — its tailwheel landing gear. For those who operate in the hinterlands of the world, the 180 offers the advantage of better short field performance and an adaptability to the rough that the Skylane, with its more delicate nose gear, can only envy.

Regardless of whether you need off-airport capability, the tailwheel configuration is attractive to a certain contingent of pilots for whom practicality is less important than tradition, a straight vertical stabilizer is more attractive than a swept tail and where you can land is more important than how easy it is to do so.

In contrast to Jack Pardo’s workhorse, ridden hard and put away wet after practically every flight, the 180K I flew for this report is a true pampered princess. One of the very last Skywagons built by Cessna in 1980, it probably has never seen a boggy tundra meadow or a chuck-holed dirt runway in its short life. Mounted on 6.00-6 tires, the test airplane even sported wheelpants, an uncommon luxury on Cessna 180s that more typically favor unfaired, oversized bush tires. This 180 had never been exposed to the abuse of the boonies. It was about as nice an example of a Cessna 180 as you’re liable to find.

As much as I love taildraggers, I’d be one of the last to advocate that everyone fly them. Nosewheel airplanes are far easier to handle, especially in crosswinds, and most pilots aren’t willing to accept any more challenge than they have to in aviation. There simply aren’t that many conventional gear airplanes around anymore. American Champion, Maule, Waco, and Aviat continue to produce the type, although it’s to a shrinking group of enthusiasts, and good used examples of the Cessna 180 are becoming scarce.

Still, a Cessna 180 does offer a certain charisma that is lacking in a 182, even if the 180 isn’t technically a true STOL bushbird. Both models have essentially the same cabin dimensions (41 inches wide by 47 inches tall), cruise near 140 knots, fly behind virtually identical 230-hp, 470-cubic-inch Continental engines with McCauley constant-speed props and 80-gallon fuel tanks, so fuel burn and range are almost identical. The 180 is perhaps the more flexible model, even if it’s not the easiest to fly. It’s readily adaptable to oversized balloon tires, skis, and floats; accepts rough strips with minimum fuss; and is arguably more fun than the three-legged 182.

If book specs suggest the slightly draggier 180 trades away 2 knots of cruise, it compensates with a 2-knot slower stall speed, and that may be the more meaningful performance parameter to those aviators who use the airplane in its element. Bush pilot technique sometimes demands approach speeds below the normal 1.2 VSO rule (speeds down short final at 1.1 VSO aren’t uncommon), and because deceleration and braking are disproportionately extended by a higher approach speed, every 2 knots off the bottom of the envelope counts.

That may be part of the reason the 180 can be grounded and braked to a stop in 500 feet, which is about 80% of the Skylane’s max short-field effort. The Cessna NACA 2412 airfoil used on the Skyhawk also serves well on the Skylane and Skywagon. Another slight advantage may be that the Cessna 180’s three-point landing stance automatically places the airplane in the optimum drag configuration to minimize rollout.

Both models benefit from the type’s plentiful aerodynamic stall warning and docile payoff. All the Cessna 180/182/185 series airplanes allow the pilot to read the onset of stall down to a knot or two and judge the approach accordingly. If you needed to sandwich the airplane into a super short strip, you could do so without fear of an unexpected stall.

Few airplanes can leap back out of the same space they came into, however, even granted the advantage of lighter weight because of off-loaded cargo. According to the pilot’s information manual, the Cessna 180 needs 625 feet to break ground from a paved, dry runway, and such surfaces are a luxury for 180s more often than not. Almost sadly, I couldn’t find an acceptable grass strip for my flights, so I had to settle for standard asphalt.

Of course, most bush strips have the disadvantage of obstacles blocking the approach or departure end (or both), and our pair of Cessnas don’t do quite as well at clearing the ubiquitous stand of trees, scoring a horizontal distance about 2.5 times the landing rollout.

That’s all just fine, you may be thinking, but what does it mean to the average pilot who wouldn’t even consider taking on a strip shorter than 2,000 feet? Well, for one thing, that strip can be liquid. The 180 is readily convertible to floats, and with several companies offering amphibious pontoons, owning a 180 gives you the option to explore that exciting other aspect of aviation — water flying — without sacrificing landings.

Operating from water runways certainly isn’t everyone’s bag, but if you buy a standard Skylane you’ll be confined to standard, hard runways forever. Amphibious floats can cost a fortune and they reduce both cruise speed (20 knots) and payload (157 pounds), but they qualify the 180 for more than one water landing.

If this sounds as if I’m bad-mouthing the standard Skylane, that’s definitely not the case. Cessna’s 182 is one of the best everyman’s airplanes ever built, and it’s a joy that they’re being made once again and probably will continue in production for another decade. The 180 just seems to have a few advantages.

Another apparent advantage of the 180 over the 182 (depending upon whether you’re buying or selling), is a considerably higher used value. A representative Cessna 180 sells for about $85,000 these days, whereas a ’76 model 182 goes for about $44,000, according to Price Digest. Using 1976 airplanes as representative, Price Digest suggests an average-equipped 180 costs about $97,000 compared to $69,000 for a similarly equipped 182. In other words, a 180 is worth roughly 45% more than a comparable 182.

Some pilots may say “so what,” and that’s a fair question. No matter how pilots such as Jack may praise their 180s, the fact is that taildraggers are slightly trickier in nasty crosswinds. My first three airplanes were tailwheel machines and though I never ground looped one, I did put the first of those, a Globe Swift, on its nose trying to avoid a kid chasing a dog across the ramp at Long Beach Airport (LGB).

Money is always the ultimate bottom line, but in the case of the 180 it may not be so definitive. After all, if you’d asked Jack what he would have taken for his 180, he simply would have laughed as he turned and walked away.