By Scott Sellers

Using Inspection Photos to Lower Maintenance Costs and Improve Safety

Given the value and safety borescope imaging brings to monitoring the health of our aircraft engine cylinders and airframe, we will explore the subject here. This Part 1 article’s objective is to explain how borescoping can help you reduce the cost of maintenance while improving the reliability and safety of operating your airplane. Part 2 of this topic will include instructions on how to perform cylinder inspections with a borescope.

Also check out the fourth episode of the Beyond the Hundred Dollar Hamburger podcast (cessnaowner.org/scott-sellers-podcast), where my brother Mark and I discuss borescoping with Dave Pasquale of Pasquale Aviation. Dave is an early adopter, longtime user, and innovator with the borescope, who spoke on the subject at AirVenture this year. Note that while I own both a Piper and a Cessna, the podcast is found on our COO website.

What Is a Borescope and Why Is it a Valuable Tool?

According to the former advisory circular AC 43-204 Visual Inspection of Aircraft (pg. 127), a borescope is a long, tubular, precision optical instrument, with built-in illumination, designed to allow remote visual inspections of internal surfaces or otherwise inaccessible areas. Borescopes allow us to see areas we otherwise have no access to inspect and create a digital history, allowing comparisons to be made as conditions change.

TCM’s Service Bulletin SB03-3 explains, “The purpose of the borescope cylinder inspection is to provide a visual method of examining the internal cylinder components and must be used in conjunction with the differential (compression) pressure test.”

Borescopes allow for viewing of the following key maintenance items:

The borescope images we shot for this article were taken with a Vividia Ablescope VA400. We have used it since 2013 on our airplanes, with good results.

Borescoping Cylinders

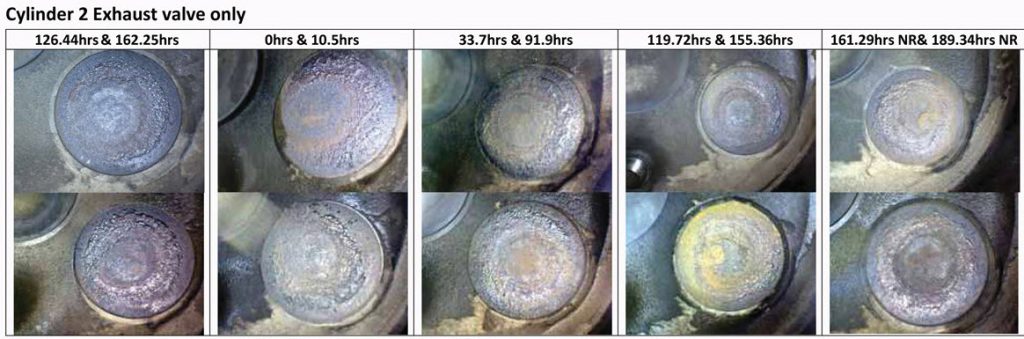

Borescoping permits the mechanic and owner to view the conditions inside a cylinder. This is a much better way to evaluate how valves are performing than a compression test alone because combustion leaves different-colored heat signatures on steel valves depending on temperature and how the heat is being distributed around the valve.

If the heat is being distributed uniformly around an exhaust valve, it will result in a “bullseye” appearance. You will see even concentric rings, which indicate that the heat is being dissipated from the center of the valve to the edges, and then onto the valve seat when the valve closes and makes contact with the seat.

When this transfer of heat is interrupted, the heat begins to concentrate in certain sections of the valve edge, and that additional heat changes the color of the top of the valve and may even alter the shape of the valve by warping it. If allowed to progress, this will result in a “burned” valve that will not hold any compression. In the most extreme cases, it can cause pieces of the valve edge to come off, or even for the valve stem to break catastrophically.

Because valves have a life cycle, and the end of that life cycle can be expensive or dangerous, borescoping permits an owner to intervene to take a valve out of service or lap it at the right moment. Such timing avoids the financial risk of taking an acceptable cylinder out of service too early, or the risk of flying on a cylinder near destruction. Early detection of valve issues changes the way we maintain cylinders and allows us to take corrective action before the valve becomes unairworthy.

Uneven heat signatures appearing on valves will occur well before compression drops off, so compressions tests are not necessarily an accurate measure of cylinder health. Because cylinder compression numbers can vary widely for many reasons, some GA industry experts suggest borescope images are a better measure of cylinder health than compression tests alone.

A lot like oil analysis, which is about identifying trends, a single picture of a valve has limited value. A skilled mechanic will prefer to look at a series of borescope images at various intervals. A borescope report at annual inspection is a best practice for tracking cylinder condition.

Borescoping Cams and Lifters

All is not the same for Continental and Lycoming engines when it comes to borescoping. Because Lycoming cams and lifters are on top of the engine above the crankshaft, while TCM engines locate the cam and lifters below the crankshaft, access for borescoping varies by brand and engine model. Cam inspection is possible on sandcast Continental engines and Lycoming engines with the short oil filler/dipstick tube in the top of the engine case. Many Lycoming 540 versions have this oil filler tube. The small oil filler tube needs to be removed for better access.

With the small oil filler tube removed on the top of our Lycoming IO-540-K1G5, here is a borescope shot of the cam and lifters:

The four-cylinder Lycomings (320 and 360 series) can be difficult to borescope the cam and lifters due to poor access for positioning the scope. The 0-320 on our TriPacer does not allow such access.

Borescoping Takeaways

- Request a cylinder inspection report from your A&P/IA at your next annual inspection

Your mechanic should provide photos at a minimum. Photos should match a standard set of photos as closely as possible. The goal in the borescope inspection is to take the same set of photos in the same way every time. This will allow the photos to be shared with people who are able to interpret them. This is similar to what is done in the medical industry. For example, an ultrasound tech will take a standard set of images for a specific reason and a doctor will review those images.

- Interpreting borescope images

Technicians who are unsure how to interpret borescope images should seek assistance from those with experience. Resist the temptation to pull a cylinder after discovering an unknown visual anomaly, as it may be unnecessary.

- How often should you borecope you cylinders?

Dave Pasquale recommends 100-hour inspection intervals for normally aspirated engines. Consider 50-hour inspection intervals for turbocharged engines. Any valve or cylinder that has anomalies should be inspected at no more than 25 hours.

You Can Do This!

Borescoping is an ideal owner-performed preventative maintenance item. I’ve successfully used a borescope on cylinders, cam and lifters, and airframe items since 2013. Give yourself some time to learn — about three +/- hours. Once you have some experience, you can share images with your mechanic to improve your airplane’s preventative maintenance.

Borescoping Is a Key Pre-Purchase Inspection Tool

Knowing the condition of cylinders, cam and lifters can be important for price negotiation and confirming the value of an airplane you are looking to purchase.

For hands-on owners, borescoping is a worthwhile practice for monitoring engine health to greatly increase safety and reliability. For those who prefer not to participate in your airplane’s maintenance, request your shop and A&P/IA use a borescope. We will get into the details of cylinder borescoping in Part 2.

TIPS FROM THE PODCAST

Scott Sellers, owns both a Cessna and a Piper, and his brother Mark periodically record podcasts (cessnaowner.org/scott-sellers-podcast). A recent one featured Dave Pasquale of Pasquale Aviation, and member of Savvy Aviation’s account management team. Here are some tips from that podcast.

Continental Quoted at Event in 2014: “If your mechanic isn’t borescoping your engine, you need to get a new mechanic.” Mark Sellers was at AirVenture in 2014 (or so) and, as he typically does, he went to the talk by Continental. He distinctly remembers the speaker saying that quote.

Mark then nudged Dave Pasquale into borescoping Mark’s engine. Pasquale has since developed report templates and become an expert on the practice. “If it has an uneven heat signature on the exhaust valve, you’re going to want to recommend lapping the valve, or depending on how bad it is, recommend cylinder replacement, or inspect again in 25 hours,” Pasquale said. “These cylinder inspections have completely changed the way that I change or maintain cylinders.”

Year-over-year pictures are great for trend monitoring, but picture quality is crucial. The patterns and trends that develop in the pictures are a great predictor of where your engine is headed, but you need a mechanic who knows how to get good pictures. “You’ll get pictures of half a spark plug, half a valve, or just the head, or just a picture of the cylinder wall,” Pasquale said. “And it’s blurry. And they’re charging the owner $200 to do it.” So, find a mechanic who’s good at this, then keep your photos on your computer.

Example of what you can learn: Hidden problem with bad lifters. “We had a friend with a Bonanza, whose oil analysis was fine,” Scott Sellers said. “Turned out his lifter faces were all pitted, while everything seemed normal.” That’s a condition that Dave Pasquale said is common and is something that can be caught by a borescope. “I would guess that probably 30 to 40% of the airplanes out there, at least in my area on the East Coast, are flying around with undetected damage to cams and lifters.” As a result of borescoping, Pasquale has “changed quite a few lifters to try to prolong the life of the cam lobes in a lot of airplanes. A lifter is maybe $100 to $130 range. Compared to an engine teardown…”

How often do you need to borescope your engine? “For most engines, annual inspection or 100 hours is going to be sufficient,” Pasquale said. “If you’re running a turbo, they seem to burn valves quicker than normally aspirated engines, so we recommend borescoping every 50 hours. And it’s super-important to do one during a pre-buy.”

Can active, DIY, owner-assisted-annual types do their own borescoping? Yes. “As long as you are capable of getting the cowling on and off correctly, and pulling spark plugs and putting spark plugs back in correctly, I think it’s a great idea,” Pasquale said. “Most pictures that I get from people are from owners, and in general, those look better than what I get out of mechanics.”

Scott Sellers has been a Cessna single-engine owner since 1995 (Cardinal, 182P, 182RG) and a pilot since 1975, all thanks to his wife Cindy, who tolerates, supports, and still enjoys flying after all these years. This series involves Sellers updating and upgrading his new-to-him 1978 Cessna 182RG.