Forget about High Fuel Costs…

Forget about High Fuel Costs…

Fly on INPULSE and SAVE!

Innovative STC Safely Uses Auto Fuel and Saves Operators Thousands in Fuel Expense

By Jim Cavanagh

Today’s fuel prices are reminiscent of the Whac-A-Mole arcade game: When a good price pops up, you just gotta hit it! It didn’t used to be like this. I remember when fuel prices began to escalate and everyone said, “No big deal…buying gas is the cheapest thing you can do with your airplane,” but now I wonder. If you stop in at a big airport and go to one of the jet FBOs, your wallet is their very least concern and paying $7+ per gallon is not uncommon.

It’s bad enough if you’re a sport flyer with a little 150-hp. (or less) engine that drinks about eight gallons an hour, but when you get up into the working or cruising airplanes with larger engines and you’re looking at 14-28 gph, it certainly becomes a factor. Anything with a CMG -550 is burning 40 gph on takeoff for a few minutes. Naturally, there are a lot of airplanes out there that aren’t being flown very much because of fuel costs; and in Europe some airplanes don’t fly at all! The result is not only a lessening of piloting skills, but inevitable corrosion damage and start-up wear can create safety concerns when they do fly—not to mention the out-of-pocket expense owners must pay to address such issues.

Even if you own an airplane for business and can write off some or all of your expenses, fuel costs influence your bottom line. Maybe, in a few years, $600-700 per fill up will constitute a “happy” number—but not today. While there are “tricks” to getting the most out of your fuel (e.g. running LOP, over-inflating tires, adding speed mods, adjusting cruise climb rates and speeds. (Go faster at a lower climb rate, or slower at a higher climb rate, depending on trip profile, etc.), in the end you have to burn fuel to get performance.

There is, however, another way to cut down on fuel costs. If you have a high compression engine or a turbo, you need to take a look at INPULSE from Air Plains (www.airplains.com).

I get into trouble on a regular basis for stating my opinion, and my Facebook page often reads like Jerry Springer or Family Court. Regardless, I’ll state right here and now that I think Air Plains’ INPULSE system is the smartest and coolest thing out there for owners and businesses who want to save fuel dollars—it’s smart; it’s proven; and it’s certified on a few airplanes, with more on the way.

For the price of one radio, you can fly auto fuel in your airplane—no matter what engine you have. Air Plains has an agreement with Peterson to build and sell the systems, and they’re currently working on multiple STCs for a number of aircraft applications. As with anything new or different, there are a few problems, but most of these are physical, and supply items can be worked out by the owner.

Now…on to the full story. Back in the 1980s, a company in Minden, NE, was selling STCs for auto fuel. Todd Peterson and his dad were the innovators who decided to jump through the Fed’s hoops and prove that auto fuel would work in aircraft and that money could be saved. Their plan worked. For the $150 price of the STC, owners could save/recoup this amount in just a couple fill-ups. They sold a ton of STCs and these kept the smaller engines flying at a high rate of hours per year. Some time ago, I successfully tried burning 91 octane in a Lycoming O-360-A4K just to see if it would work and I had absolutely no problems.

Peterson’s program was so successful that the EAA also began an AF STC program. In fact, you’d be hard pressed to find an airplane of that era that doesn’t have an auto fuel STC sticker somewhere on it. However, there were problems and limitations.

While an STC outlines how you should operate an aircraft on auto fuel and these directions apply to specific models, some certified aircraft simply cannot burn auto fuel—for mostly physical reasons. For example, many would vapor lock on hot days and after prolonged ground ops. The thing about auto fuel is that isn’t “designed” for aircraft. In addition to there being varying “seasonal blends” of auto gas, you have to understand that auto fuel has different vapor pressure ratings and lower anti-oxidant levels as well. It can also create a lot of varnish in a fuel system if the plane just sits. It’s also worth noting that auto fuel is only good for up to a one year before it begins to degrade.

Smaller aircraft were fine, but anything with a higher compression engine couldn’t burn anything but 100 octane fuel; and to get this, Tetraethyl Lead (TEL) had to be added. Worse yet, the auto fuel itself began to change as states pandering to the Ag lobbies began requiring a certain amount of ethanol be blended into gas sold at the pumps. Of course, ethanol has far fewer units of energy per volume than petroleum fuel, thus it either reduced range or called for larger fuel tanks, plumbing, and carb jets. Performance remained the same, but fuel burn increased considerably.

This threw all fuel specs out the window. Straight fuel could (and can still) be found, but you had to look for it and ask the vendor—a ponderous and dumb, ergo, unpopular alternative. The availability of straight fuel dropped; and with the odds of pilots using incorrect fuels, auto fuel STCs began to lose favor. Even the EAA eventually dropped their program.

Auto fuel can still be used successfully in smaller engines—87 octane in engines with less than 8:1 compression cylinders and 91 octane for 8.5:1 compression jugs (160/180-hp. engines for the most part). That’s IF you can find pure fuel that is unadulterated with ethanol—not that it won’t provide enough power, rather your aircraft systems might not be compatible with the alcohol. Plus, ethanol is not an approved fuel. But I digress…

Back when auto fuel was a viable, daily-use alternative, the Petersons were working on ways to get auto fuel into the bigger, more powerful engines. Having been in the Ag business, they knew that working airplanes would one day be priced out of business by the trend of rising fuel costs. This was also about the same time 600-700-hp. turbine engines burning Jet A fuel (which is traditionally less expensive than avgas) were coming into vogue.

What Todd and his dad came up with was the reintroduction of technology from the 1930s and 40s. Developed to its full potential for military aircraft during WWII, Anti-Detonation Injection (ADI) was the way engineers kept aircraft engine cylinders from melting under high power settings. A mixture of water and oil was injected into the cylinders to cool them and, in effect, added a modicum of steam power to the compression stroke. It worked during the war and has also worked in a number of commercial aircraft engines over the years.

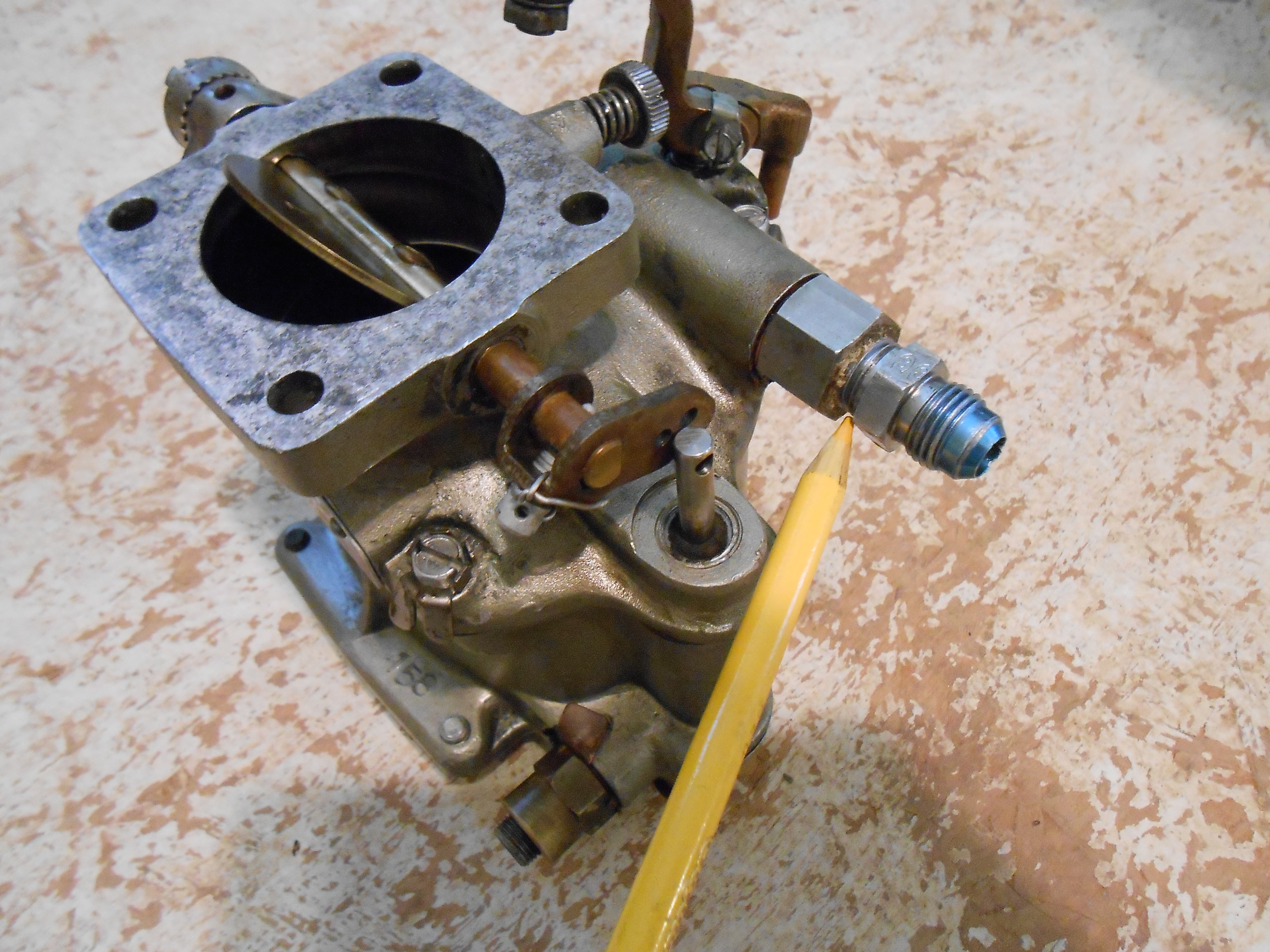

The Petersons concocted a formula of water, water-soluble oil, and methanol, and then designed sensors and a delivery system that allows engines to run on fuel well below 100 octane. Manifold Pressure and CHT sensors connected to a small computer trigger pumps (primary and backup) that automatically deliver the mixture to the cylinders when needed.

The mixture provides water for cooling, oil to eliminate any oxidation formation in the cylinder, and methanol to keep the mixture from freezing at altitude or during cold weather. The mixture is stored in a five-gallon tank aft the baggage bulkhead. A filler port, along with a graduated dipstick to check the level, is located on the fuselage. The above-mentioned primary and secondary pumps are located at the tank, and everything is mounted on a platform that bolts to the fuselage. The pumps are custom made for Air Plains, as is the panel-mounted computer that controls everything.

The engine compartment looks basically the same, with the ADI mixture being delivered to the throttle body and mixed with the fuel. If there is a problem, an indicator light comes on and the pilot simply uses reduced throttle settings for the remainder of the flight. Since the system is automatic and only used when cylinders approach the detonation point, the five gallons of fluid can last for many, many hours of flight.

The entire system costs just under $10,000. Air Plains will provide the ADI mixture or the owner can use the “recipe” included with the paperwork to make his own for a couple of bucks per gallon.

Still, as good as this all sounds there are a couple things an INPULSE customer will have to contend with—not really “problems” per se, rather items that must be considered when doing something non-standard with an airplane. First, there are only three (soon to be four) airplanes that have been granted STCs by the FAA. The Beech Bonanza, B-55 Baron, and Cessna C-188 Ag Truck have been approved, and a Cessna 180 is just finishing up its test period.

I flew the 180 with a factory pilot and aeronautical engineer, Rafael Soldan. The airplane had been modified with an Air Plains’ 300-hp. conversion. In spite of the ear popping climb, the flight was pretty “ho-hum” if you were looking for a lot to do to operate the INPULSE system.

The small panel, mounted just left of the pilot’s yoke, has a couple of lights to tell you that the system is in operating condition (pre-flight) and that it’s armed and ready. With sensors monitoring both Manifold Pressure and CHTs, the pumps would kick in and a light would come on when either approached the detonation threshold. Then, as power was reduced, the system would go off line. (It was on very briefly during the takeoff—surprising me that so little power is actually used when the plane is lightly loaded). There is really nothing for the pilot to do. IF the system goes off line, simply pull back on the power and operate at 65 percent.

Note: If you really want to understand how an engine works (vis-à-vis fuel and ignition), the Professional Pilot’s Course taught by GAMI will take you inside an engine where all the work happens. GAMI has studied this in depth at their Ada, OK, facility. All of their LOP numbers are empirical and complete.

If you’re interested in INPULSE, consider the following:

- You’ll be burning fuel at half the cost of avgas.

- You’ll be able to run your airplane on avgas or mogas (legally) for the rest of your life.

- You’ll save up to $45/hr/engine, and on a single engine airplane expect to save $45,000 every thousand hours. Now that’s a BIG number!

- Plus, aside from keeping the tank loaded with fluid, you won’t have to anything to run the system!

Your biggest challenge will be actually getting the auto fuel as airports discontinue handling it. Even if the airport does have mogas, they probably price it just a buck or so lower than their aviation juice. To really save, you may have to provide your own fuel, and the problem here is whether or not the airport will let you bring it to the field and/or store it.

If you have to buy your own gas, you need to find a source with good clean fuel and, ideally, no ethanol. You will then have to transport it to your airport and get it into your airplane. If you invest in IPULSE, the next investment should be a gas trailer so you can take 300-500 gallons to the airport. Five-gallon cans are a LOT of work, messy, dangerous, and time consuming. Katie Church, the Marketing Manager for INPULSE at Air Plains, has information on commercial tanker trailers. Owners based at home strips and small airports might not have a problem, but larger airports like to protect their profit lines with city or county ordinances. Check these things out thoroughly if you get serious. I would apply for a waiver—particularly if you use a DOT trailer.

Really your only other way to save on fuel costs is to convert to diesel—that’s IF you can find an engine big enough, and IF you can afford the tremendous price of the conversion. Nothing in life comes without some sort of tradeoff, but INPULSE seems to be the smartest thing a guy can do at this point in aviation to get back to comfortable costs for your flying.

Finding 91 Octane Fuel

According to recent studies, 80% of piston powered aircraft have the ability to run on unleaded ethanol free fuel. Yet, although high octane unleaded auto and biodiesel fuels for piston engines have been safely and successfully used in Europe for many years, adoption in the U.S. has been slow.

Unfortunately, airports face a number of significant barriers to offering fuel alternatives. A general lack of pilot education, uncertainty about liability coverage, and concerns about the supply of high octane unleaded fuels that are ethanol free are but a few such obstacles.

Nonetheless, over the past 3 years the number of U.S. airports offering mogas has been on a positive trend. In fact, some airports are starting to offer ethanol-free mogas simply because the price of 100LL has been on a steady rise

If you’re planning a cross-country flight utilizing mogas, AIRNAV.com offers a great tool to plot the best routes. Of course, as with any cross-country planning, it’s always a good idea to call ahead to check fuel availability—no matter what your fuel of choice is.