All photos taken by Jack Fleetwood (www.jackfleetwood.com)

By Michelle Adserias

Harold Kennedy took his first flying lesson when he was fifteen years old. He was hooked! He might have missed this early opportunity, but his father was learning to fly and his mother, who feared her husband’s flying skills would mirror his driving skills, wanted to be sure someone else knew how to land the plane safely.

Harold continued taking flying lessons. On his sixteenth birthday, a year after his first flight, his parents took him to the airport where the instructor signed his student certificate and logbook and handed him the keys to go solo.

It was another year before Harold got his PPL. He worked 48 hours a week refueling planes, nights and weekends, throughout high school. Minimum wage peaked at $1.65 and Harold was thrilled to get a five cent an hour raise. He used his earnings to pay for more flying lessons, during which he logged time on a multi-engine Apache trainer. On his 17th birthday, Harold got his PPL for single and multi-engine planes.

He purchased his first airplane, a J-3 Cub, when he was just 18 years old. By the time he got married, he was flying his fourth plane, a Cessna 182. He and his wife flew it to their honeymoon destinations in Durango, Colorado, and the Grand Canyon.

The next step in Harold’s journey was refurbishing and flying corporate jets. He purchased airplanes for customers then oversaw the needed cosmetic and avionics upgrades. In 1989, he moved into the commercial world, flying for United Airlines. He has since retired and continues flying for his own enjoyment.

The Riley Turbostream

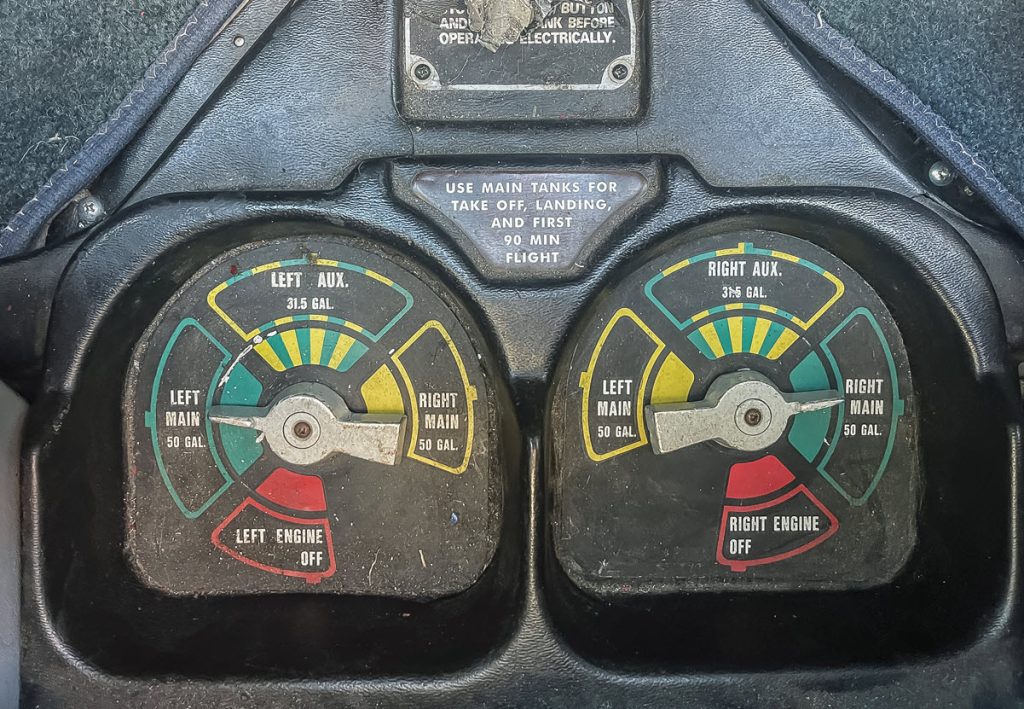

As an avid fan of the old TV series, Sky King, it was fitting that his 27th plane was N100EL, a 1973 Cessna 310Q. It was converted to a Riley Turbostream in 1975 when the original 260 hp Continental IO-470-VO engines were replaced with 350 hp Lycoming TIO-540-N2BD counter-rotating engines under an Experimental Airworthiness Certificate. The certificate was issued for a year and was restricted to day or night flights within 100 miles of Waco, Texas. A Standard Airworthiness Certificate was issued in the normal category shortly afterwards, once the test flights were completed.

Harold already owned a Cessna 310R. His only concern with this plane was its long nose, which made it impossible to store in a standard T-hangar. The sometimes-inhospitable Texas weather made it risky business to tie down the airplane outside. At some point, it would sustain hail damage. He placed a “Want” ad for a Cessna 310Q, which has many of the same R model upgrades, but has a shorter nose and less power.

He received a call from a woman settling her father’s estate. She wanted to sell his Cessna 310Q, with the Riley Turbostream upgrade. Harold asked a local mechanic to check the plane over. When he got the go-ahead, he bought the airplane, sight unseen. Unfortunately, the family had allowed the plane’s FAA registration to lapse. The mechanic began some of the restoration work while doing an annual inspection during the six-month wait for FAA approval. The first two things that needed attention were the AD note on the heater and oxygen bottle. Harold had the heater removed and sent for the AMOC (Alternate Means of Compliance), then replaced the expired oxygen bottle.

When the plane was once again registered, Harold flew it from California to Central Texas Avionics in Georgetown, Texas. There, a long-time business associate continued working on the restorations between his bigger jobs. That flight is Harold’s favorite memory of N100EL. As a matter of caution, he made the flight alone. He even declined the mechanic’s offer to go up for a short trial flight – though the mechanic’s willingness did give Harold added confidence the plane was flightworthy.

Upgrades and Alterations

Of course, the big change to this Cessna 310Q was the Riley Turbostream upgrade, but Harold has made some other changes as well – mostly to the instrument panel, which he essentially overhauled. Mechanically and cosmetically the plane was in great shape, but Harold wasn’t happy with the avionics. Before flying it home to Texas, he watched a few tutorials about the Apollo CNX-80 and remote transponder to familiarize himself with the system. Since the technology was no longer supported, and Harold is a self-proclaimed “button pusher and knob turner,” he replaced the Apollo CNX-80 with a Garmin GTN-750, and the transponder with a Garmin GTX-345 transponder with In/Out to display traffic and weather on the GTN-750.

Harold kept the existing weather radar that was installed to supplement the ADS-B weather and the Bendix/King KX-165 as the #2 Nav/Com. He added two Garmin G5’s as an Attitude Indicator and HSI, and also replaced the audio panel with a Garmin GMA-345. In order to make room for these new avionics, he added two Garmin GI 275’s as the Engine Indicating System, which replaced seven 3.25” panel instruments.

What’s next? Harold would like to install a GFC 600 Digital Autopilot. He attended a Garmin autopilot seminar at AirVenture last year, where Garmin suggested the autopilot would be approved for the Cessna 310Q within twelve months. He would also like to replace the wing boots.

Flying and Maintaining N100EL

Though Harold flies 40-50 hours each year, he hasn’t taken any long trips in N100EL since flying it from California. He finds this airplane comfortable, with a larger cabin than his B-55 Baron. He also appreciates the wing lockers, for storage, and is intrigued by the claim Jack Riley’s upgrade makes the plane capable of 300 mph at 18,000 feet. It doesn’t sound like he’s tested that claim yet.

Because he has flown N100EL a limited number of hours, the per hour cost is currently, in Harold’s words, “scary.” He budgets $6,000-$8,000 per year for maintenance. His fuel burn is 42-44 gph for both engines, so he plans $250 per hour for fuel.

As of yet, Harold has not run into any problems maintaining N100EL. Because the engine is still supported by Lycoming, parts are readily available. When he was looking for replacement legs for fifth and sixth seats, he got a “good luck” from a local shop owner, who suggested he try salvage yards. That wasn’t necessary. He found an online Cessna dealer, Yingling Aviation, and had the parts in a few days.

The top, rotating beacon was replaced with a Whelen LED strobe. Since the strobe is lighter than the beacon it replaced, and is attached to the rudder, which is a balanced control surface, the mechanic had to make some adjustments.

He feels the most important aspect of maintenance and care is listening to your plane. “It will tell you when something needs attention.” It may make a different noise, or the EGT or CHT may be higher than normal. A good engine analyzer helps pinpoint the problem causing the changes and will help you troubleshoot. Once your mechanic finds the problem, give him time and space to work. It’s better to spend the night somewhere than to rush a repair. “Always err to the side of safety.”

Final Thoughts

Owning a Riley converted airplane, a piece of aviation history, has given Harold a sense of responsibility to preserve this airplane.

Harold shared, “Today’s pilots probably never heard of Jack Riley but he is credited with taking an airplane and improving its weak areas. Mr. Riley once said, ‘There is no substitute for horsepower.’ Riley’s upgrades have given added power to several Cessna models including the 210, 337, 414, and 421’s.”

The rest of this article and this plane’s specifications can be seen only by paid members who are logged in.Have a website login already? Log in and start reading now.

Never created a website login before? Find your Customer Number (it’s on your mailing label) and register here.

JOIN HERE

Still have questions? Contact us here.