Airplane engines seldom just stop, but one of the fastest ways to stop an aircraft engine is to remove the fuel source.

There are two terms that apply to this discussion:

“Fuel Starvation” refers to a situation when there is fuel in the tanks but, for some reason, it is not getting to the engine. This is typically the result of a mechanical failure, but mismanagement of fuel tanks is a factor, especially on an aircraft with more than two tanks.

I had a Cherokee Six from 1986 through 1992 with mains and tip tanks. In 1988, after an abrupt career change, I decided to clear my head and left Hartford, Connecticut with plans to fly across the country to Pebble Beach in Southern California. I typically flew eight hours a day; four hours before lunch and another four in the afternoon. There were a lot of tank changes and I typically set a timer to remind me. I had no issues.

Mishandling of the tank selector valve can stop an engine. I read about an accident investigation where they found the valve position set between two tanks that ultimately resulted in fuel starvation and a fatal crash. Sadly, aviation accidents as a result of fuel starvation are more likely to result in a fatality, as the pilot, knowing they have fuel available, focuses on restarting the engine instead of finding a good place to set it down.

“Fuel Exhaustion” refers to a condition where the aircraft becomes totally devoid of usable fuel. Running out of fuel is almost always the result of human error and frequently results in an off-airport landing, often a mile or two from the destination airport. Pilots who find themselves in this situation have only one option; to focus getting the aircraft on the ground. Yet, a quarter of these accidents happen at night when the task is considerably more difficult.

Fuel exhaustion is easier to prevent. Check your fuel before you leave. Budget extra time for fuel stops. Know your usable fuel and burn rate: this can be an issue for a pilot flying an unfamiliar aircraft. And when you find yourself low on fuel, don’t hesitate to declare an emergency. The FAA also suggests you make use of available fuel monitoring technology. Let’s talk about that!

Fuel Gauge Sending Units

One article I read while researching this topic boldly stated: “Blaming your accident on a bad fuel gauge doesn’t cut it!”

However, many pilots simply don’t trust their old fuel gauges and while updating their avionics, especially when including expensive primary engine management units, are also upgrading fuel tank sending units. Let’s look at what the aircraft manufacturers provide and what the options are today for upgrading fuel level sending units.

Resistive Fuel Quantity Senders. I’ve owned 35 cars in my 57 years as a driver and I’ve put a wrench to most of them. That included occasional replacement of a faulty fuel pump or quantity sending unit. The old sender often showed a lot of wear and some corrosion. I wasn’t surprised it was unreliable when I saw it. Mechanical resistive senders are very vulnerable to water or moisture in the tank and signs of that were obvious.

The technology I saw in my 1996 Audi is pretty much what you would find in your legacy Piper or Cessna. The mechanical sending unit has a float attached to an arm that rubs against a variable resistor (potentiometer) and sends this signal to your 50-year-old mechanical gauge. The other downside is that there are electronics inside the fuel tank with this technology. Bottom line: These units are subject to deterioration as they age so it is very likely you are not getting accurate information. New replacement resistive senders of this type for Piper or Cessna can be found online in the $500 price range.

Capacitive Fuel Quantity Sensors. The heart of this system is a capacitive sensor located within the fuel tank in the form of a vertical tube. There is no float. The capacitance between the two plates of the capacitive sensor changes as the fuel level changes. When the fuel level is higher, more of the non-conductive plate is immersed in fuel, altering the capacitance. The converted electrical signal is sent to an electronic control unit (ECU) or processing unit. The ECU interprets the signal, converting the voltage or frequency reading into an actual fuel level measurement. Like the analog resistive sender, there are electronics in the fuel tank with most systems. Capacitive systems are also analog, but they are more accurate, less vulnerable to wear, and are typically more expensive to install.

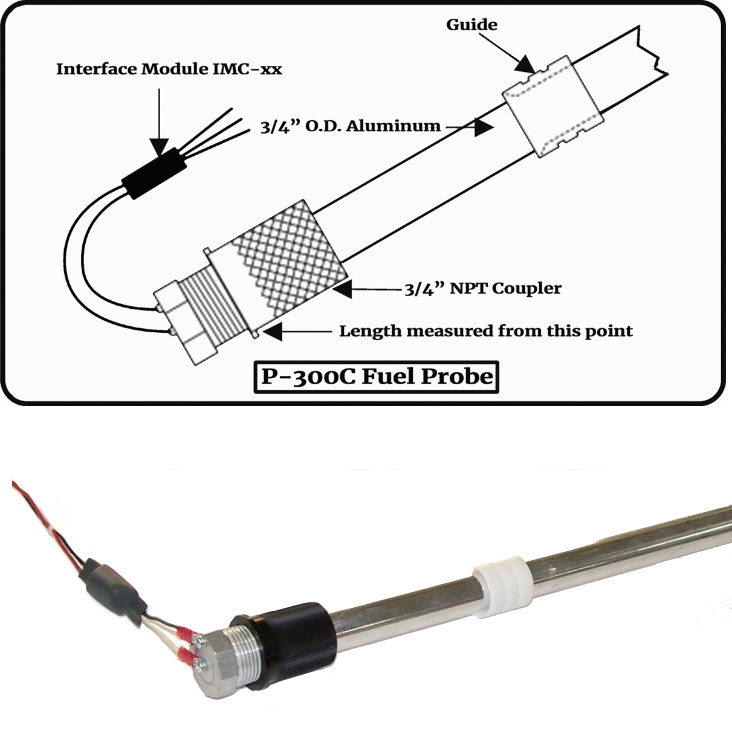

Electronic International (EI) offers the P-300C capacitive fuel sending option that is compatible with their CGR-30P or MVP-50 integrated engine management systems. The CGR-30 and MVP-50 will work with your original resistive or their capacitive option sending units. EI’s P-300C appears to be a hybrid in that the design (vertical tube) is consistent with other capacitive systems but the probe uses magnetics to measure fuel level, and it does not have electronics in the tank.

This is different technology than you will find in the CiES senders below.

The rest of this article can be seen only by paid members who are logged in.Have a website login already? Log in and start reading now.

Never created a website login before? Find your Customer Number (it’s on your mailing label) and register here.

JOIN HERE

Still have questions? Contact us here.