Preparing for the Unthinkable

By Scott Sherer

I read all the aviation-related publications I can get my hands on, and I watch every aviation-related TV show and movie I can find. I have my DVR set to record two TV shows in particular. The Weather Channel has a show titled Why Planes Crash and The Smithsonian Channel has a show titled Air Disasters. Each show reenacts aviation catastrophes that go back many decades. Both networks are credible, and their shows are realistic. Sometimes I have difficulty guessing whether the video footage is real or not.

Of course, the likelihood of being in one of these events is infinitely small, but it could happen. Just like the odds of buying a winning lottery ticket is infinitely small, but we do it anyway.

So here are my thoughts on reducing the likelihood of being in one of these horrible events and how to get out of it alive and in good health should it happen. First, a caveat: I’m talking about our own airplanes and not the airlines or air charters. Second, be really careful out there. Having said that, here are my personal guidelines for flight accident risk reduction and prevention.

- Don’t spend the bare minimum on aircraft maintenance. I write the checks just like you, but if you don’t want to have to use your emergency test pilot skills, don’t have a mechanical problem. Can’t maintain your plane to safe standards? Don’t fly it!

- Don’t fly in bad weather. I’m not talking about IFR here, I’m talking about really bad weather. High winds, storms, icing, extreme precip and turbulence. And don’t combine these with night flight, as it only compounds the problem and drastically increases the risk.

- Always — and I mean always — use your checklists.

- Stay competent. I don’t mean current, as there’s a difference between being legal and being competent. Fly frequently and run your plane frequently. You both can get rusty.

- Carry current maps and charts or make sure your subscriptions are up to date. You have no idea when this will be critical.

- Go easy on prescription drugs when you’re going to fly. I haven’t read this anywhere else, but I’ve moved my daily prescriptions to 10 p.m. so when I fly there are at least 12 hours between taking my prescriptions and my throttle.

- Other drugs? Never. Alcohol? I know the rule is “eight hours from bottle to throttle,” but I use 12 hours. No exceptions.

- Tired? Not feeling tip-top? Think you might be getting sick? Don’t fly, no exceptions!

- Feel free to add to this list. When you do, send me an email, and I’ll add your item to my list, too.

Having said all this, what happens when you get in your plane, head out on a long cross-country, and you have an emergency? This happened to me at Thanksgiving 2021. My wife and I were flying to Colorado, and we lost a magneto at 10,000 over Nebraska. It all ended well, but it was very stressful. But what would have happened if the backup mag had failed, too?

Let’s cut to the chase here and just say that you find a road or field to land in. What the emergency is and how you handle it is a subject for other articles. For the purpose of this article, you’re down and alive. You’re able to find your way out of the aircraft and you need to get help. Perhaps you’re injured or perhaps you’re out in the elements and not prepared for the challenge of survival. This, too, is a topic for another article. The topic for this article is how do I summon help? For me, the order that I have these items below is not important. I have all of them or I don’t fly. Here’s the list:

- A cellphone. This is your quickest path to a rapid response to your crisis. These days, everyone has a cellphone, so just make sure you bring it and it’s fully charged. Make sure that you have GPS location turned on in your cellphone. If you don’t, and you’re lucky enough to reach 911, they won’t know where you are. The downside is that you may not be in range of a cell tower, or your cellphone may have been damaged in your landing. Likelihood that your cellphone will get help when you need it? Not good.

- Your old 121.5/243.0 Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT). If you have an old 121.5/243.0 MHz ELT, good luck. The old SARSAT satellite that picks up 121.5 was decommissioned in 2009. If you’re transmitting on 121.5/243.0, you will be totally dependent upon either someone purposefully looking for you or someone who happens to be in your vicinity, have their No. 2 comm set to 121.5, and be close, like less than 10 miles from you. Likelihood of your old ELT getting help? Not good.

- Your new 121.5/406 MHz Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT). Last year, I purchased a new 121.5/406 MHz ELT. The Cospas-Sarsat satellite will pick up your 406 MHz signal very quickly, and the signal location will be within 3 kilometers, compared to 15 to 20 kilometers for 121.5 MHz ELTs. When you couple your ELT to your WAAS GPS Nav system, accuracy improves to about 100 meters. Battery life is typically five to six years, depending on the make and model, when unused. When in use, the 5-watt transmitter will generally run for a couple of days, again depending on make and model.

- Note that the signal transmitted by a 406 ELT is digital, and a specific identification code is transmitted to the satellite. That specific ID is assigned to you when you register your new ELT immediately after purchase via a registration website. Then, if a satellite receives a signal from your ELT, it’s forwarded to a Mission Control Center (MCC), where the staff looks up your code in a registration database to identify you. They have your contact information and next-of-kin information, so the first contact goes out immediately. If you don’t have a GPS-coupled ELT, the recovery effort starts in about an hour. If you have a GPS-coupled ELT, the recovery can start in as little as three minutes. Likelihood of this working when you need it? Very high.

- A handheld portable comm radio. I have a Sporty’s SP-400 handheld nav/comm with two sets of batteries stowed in the airplane for emergency use. Not only is it useful in this scenario, it’s also useful in the airplane if you should be unlucky enough to have a power or nav/comm failure. Or when pre-flighting your airplane, you can listen to ATIS or pick up a clearance. For $299, this is a must-have item. Icom and Yaesu also make excellent radios with prices as low as $209.

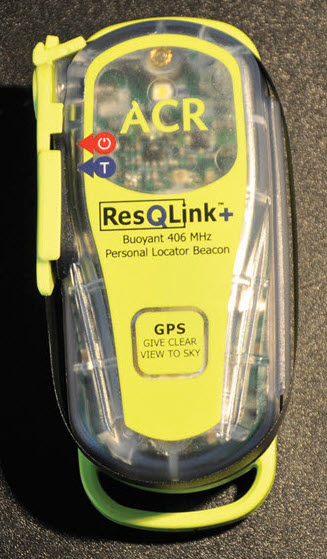

- Finally, I have a personal locator beacon (PLB). When I get in my airplane, I put this device over my head via a lanyard. This is a mini-ELT with GPS and a signal strobe light (actually a high-energy LED lamp) that’s waterproof and will float. Remember my mentioning on item No. 3 that if your ELT is GPS-coupled that your recovery could start in as little as 3 minutes? This device has that feature. With your both your ELT and PLB transmitting, you have doubled the likelihood that you’re going to be found quickly and alive. After all, if you severely damage your airplane, you may not be able to ascertain whether your ELT is working or not. You may not be able to get to it, and it may be inoperative.

- With a PLB around your neck and transmitting your GPS position, the rescue effort knows who you are, where you are, and if you’re on the move, they can follow you. PLBs are made by ACR, SPOT, McMurdo, Rescueme, and Artex and start at about $249. Likelihood that you’ll be found with this device? Very high. Cospas-Sarsat has rescued more than 20,000 people since 1982 with this technology.

- Finally, if it’s at all possible, file a flight plan. Also, make sure you tell someone you’re going flying and where you’re going. A note for a spouse, a text message or email to your kids, friend, or co-worker, whatever. If the worst happens, make sure you’ve done everything you can to come home safely and in good health.

How Do 406 MHZ and PLB Work?

Back in the day, we had 121.5 MHz and 243.0 MHz in our ELTs. 121.5 was for the public, and 243.0 was for the military. As we all know, reliability of the units was not very good, with a high percentage of false alarms. It was the best technology we had, so we installed them in our planes as required by the FAA. When these ELT units did trigger (correctly or not), the likelihood of anyone hearing your transmission was marginal.

Many of us who trained as pilots back in the 1960s were told to keep our No. 2 comm (if we were lucky enough to have one) on 121.5 and monitor all the time. If you went down on an airway where other 121.5 monitoring aircraft were flying overhead, you might have a chance to be detected.

Off airway, in the mountains, for instance, no one would hear your transmission. To improve the likelihood of being heard, the SARSAT (Search and Rescue Satellite) network was created to detect these transmissions. This improved the capture of these signals but didn’t improve the reliability of ELTs or improve the ability to home in on the signal and find you in a sufficiently short time to supply medical treatment, should you be unlucky enough to require it.

Many of us are still flying with 121.5 analog ELTs and you should know that the SARSAT satellite network that detected your ELT was decommissioned in 2009 and replaced with Cospas-Sarsat. The International Cospas-Sarsat Programme is an intergovernmental cooperative of 43 countries and agencies that maintains a network of satellites and ground facilities to receive distress transmissions from 406 MHz beacons and route the alerts to appropriate rescue authorities in more than 200 countries and territories. 406 MHz is the radio frequency in which the beacons transmit and it’s monitored around the world by the Cospas-Sarsat satellite network.

The new Cospas-Sarsat satellite network is comprised of 10 satellites. Six are in high geostationary orbit of 22,500 miles at the equator. Four more satellites are in Low Earth Orbit (LEO). When one or more of these satellites detects a digital signal on 406 MHz from an ELT, PLB, or EPIRB (if you’re on a boat), these signals are routed to a geographically relevant Mission Control Center (MCC).

Effectively, your old 121.5 ELT should be removed and replaced with a shiny new 406 ELT soon. The prices have come down on the new ELTs, and they take almost no shop time to install. There are three kinds of ELTs you can purchase. For about $600, you can purchase a replacement for your old ELT that uses the same wiring and installation tray but has no GPS capability. While this is cheaper, the signal transmitted won’t have your exact location, and the search and rescue teams will have a larger area to search for you, which will take more time.

For significantly more money, you can purchase an ELT that’s either wired to your panel mount GPS to obtain an accurate GPS position or contains its own GPS internally wired to the ELT. Either option can cost around $3,000. If you have a lot of money, this is a perfect solution to an unlikely problem.

Here’s my alternative solution. First, replace your old 121.5/243.0 analog ELT with a new 406/121.5 ELT. Don’t spend the extra money for the GPS capability if you don’t want to. Instead, spend about $200 for a Personal Locator Beacon (PLB). Wear the PLB around your neck with a lanyard when you’re flying (or boating, hiking, or parasailing). The PLB has GPS built into it. If you leave the airplane, the PLB will stay with you. If you’re injured and you turned on the PLB before your disabling event, you will know it’s working. While your ELT will probably also start transmitting, it won’t be sending your exact GPS position like your PLB will be. However, you will have two transmitters sending your position. In the unlikely event that one transmitter doesn’t work correctly, the chances are higher that you’ll be found alive and in time to save you and your passengers. If you have an old ELT, don’t plan on this.

Resources

406 MHz ELT and PLB Manufacturers

These are the major aviation manufacturers. They are available through avionics shops, Aircraft Spruce (aircraftspruce.com), and other aviation retailers. Other, lesser-known PLBs are also available.

ACR (acrartex.com)

Spot (findmespot.com)

McMurdo (orolia.com)

RescueMe (oceansignal.com)

Handheld Transceiver Manufacturers

These are available through avionics shops, Aircraft Spruce (aircraftspruce.com), Sporty’s (Sportys.com), and other aviation retailers.

Yaesu (yaesu.com)

ICOM (icomamerica.com)

Sporty’s (Sportys.com)