By Tibor Farkas and Michelle Adserias

From the time he was young, Tibor “Bill” Farkas loved to travel. When a family trip was on the horizon, in his excitement Tibor would pack a week early and ask to keep the airline tickets in his room. He thought he might even pursue a career that involved travel when he was older – perhaps maybe in sales or as politician. He really never considered a flying career until one particular trip opened his eyes to the possibilities ahead.

In the mid-1980s, Tibor and his parents flew to New Jersey to visit family. On this particular flight, the American Airlines DC-10 was equipped with a camera in the cockpit which was turned on during takeoff and landing, making almost everything the pilots were doing available to be displayed on the airplane’s cabin movie screens, thus giving the passengers a view of the pilots at work. Also available at that time was an audio channel which allowed passengers the ability to listen to the air traffic control communications during the flight through their headsets.

While on descent to Newark, and with an undercast layer of clouds below, the airliner transitioned from a brilliant sunsetted twilight to near total darkness in a matter of minutes. Just before he heard their flight receive its approach clearance through the headset, Tibor realized his view below the clouds was now of the bright lights of New York City off the left-hand side of the aircraft. Then turning towards the cabin screen, he noticed the ‘postage stamp’ of a runway on which they were to land.

As the aircraft continued its approach to the airport, he listened to their flight number receive a landing clearance, followed by the sound of the landing gear being extended. As they continued closer to the ground, Tibor noticed motion in his periphery outside of the window accompanied with a certain tension in the cabin – the ground was getting closer and none of the passengers, including Tibor, had ever seen what it was like to land a jumbo jet from the cockpit before. The view of the runway on the screen was much larger, and all involved were now very committed to the outcome.

The touchdown was amazingly smooth and the view forward was of the captain applying reverse thrust to the engines, while the copilot deployed the spoiler lever. As this huge mass of metal and people began to slow, the entire cabin erupted in applause. When they exited the runway, Tibor remembers looking towards his mother and saying, “I know what I want to do with the rest of my life. I want to be an airline pilot.”

Three months later he was riding his bicycle through the neighborhood and noticed an airplane in his neighbor’s garage. It took him a couple more weeks of riding back and forth in front of their house to get his entire 14 years of accumulated courage together. Tibor approached the husband-and-wife team who just happened to be starting an airplane refurbishing business. He began to ask many technical questions. He recalls, retrospectively, that this must have piqued their interest in him as well, which might have lead to the following offer: “We’re just in the beginnings of our business, so we can’t afford to pay you. However, if you want to continue to come over to work on and learn about the airplane, we can trade off your time spent in exchange for your private pilot ground school.” The airplane was a Piper J-3 Cub, and their offer was quickly accepted. Tibor became well versed in the mechanics of paint stripping, sand blasting, and rib stitching – all of which are necessary during the restoration of aircraft like this. Their company name became Aero Again.

Back to His Roots

Even though the first aircraft Tibor worked on was the Piper Cub, his first non-airline flight was in the venerable Cessna 170. This occurred at the Georgetown Airshow within just a few weeks of making his aviation connection with the neighbors. Mr. Dean Ogden was giving rides in a 170 before and after the airshow that weekend. It wasn’t until over 10 years later that Tibor and Dean realized they had that first flight in common, but only after they were already partnered in an airplane together.

The learning at Aero Again continued through the remainder of his sophomore year of high school. The wife was the A&P mechanic, commercial pilot, and certified flight instructor (CFI), and became his first instructor. Tibor was not only gaining knowledge about flying and the aircraft restoration process, but he also discovered that his teachers owned a Cessna 170.

They used that aircraft for running errands for the restoration business and also in the evenings for sunset flights. Their 170, N9500A was pristine – baby blue over mid-1940’s Cessna beige. The interior forward panel had an original checkerboard pattern and what is referred to as ‘piano key’ switches for the electrical components. Tibor recalls a post flight ritual of wiping down the leading edges to remove any of the bugs which might have impeded their progression through the air while in flight. His time spent in and around the Cessna 170 was memorable.

Fast-forward 25 years: Tibor has piloted over 140 uniquely different types of airplanes since his beginnings with the 170. He knew all along how generous aviation had been to him. By then, he had been harboring ideas of how he could give back for quite some time. Of all the airplanes to choose from, it didn’t take long for him to come to the conclusion that the 170 would be the correct fit to return that first ride to as many people as possible. Even though he made attempts to solicit a purchase of that blue and beige airplane from the past, he was unsuccessful. It occurred to him, “Well, it doesn’t have to be that exact 170 to make this mission possible.” So, the search began.

After nearly two years, he found N9277A, a 1949 Cessna 170A. This particular aircraft happened to be just 23 production serial numbers away from original N9500A. The aircraft was also true to its own roots with ‘piano key’ switches and a checkerboard instrument panel.

Additionally, it possessed some perks which the previous owner had so generously provided. A rear baggage door, which was not an original feature of the 170, was installed under a supplemental type certificate (STC). Other improvements included an STC modification which moved the exhaust pipes aft from the cowl cheeks to a position just in front of the firewall and retractable handles on the fuselage near the tailplane, used to more easily move the aircraft in and out of the hangar. These handles are generally reserved for the larger tailwheel Cessnas.

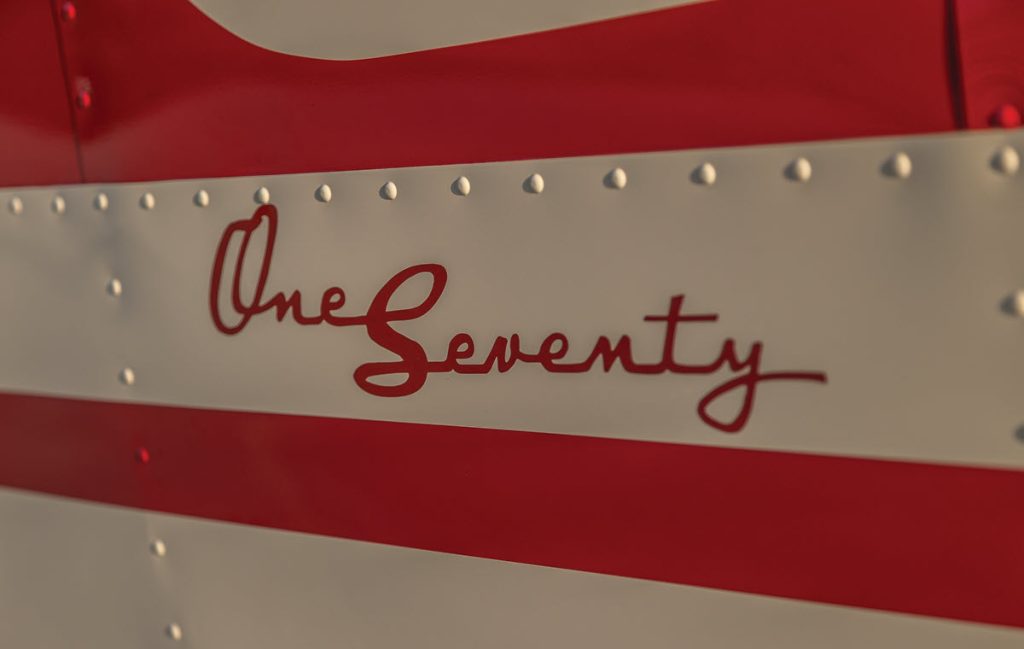

There was something missing though. Tibor said, “Even with all of these attributes, the airplane was lacking a decent paint job. It deserved it! You cannot put good paint on an uneven canvas.” In order to accommodate the new paint, the older, noticeably patched rudder and other control surfaces were reskinned along with replacing the engine cowling and nose bowl. The airplane came to him with an interior based in red, so he matched a Cessna red from the past and, of course, put it over that 1940’s beige. Tibor researched Cessna marketing from that era and combined two original paint schemes from the model 170 to arrive at the final design as it appears today. Even though the paint scheme is not singularly original, he said, “It was the best way to get a lot of color incorporated onto the aircraft’s exterior.”

Have a website login already? Log in and start reading now.

Never created a website login before? Find your Customer Number (it’s on your mailing label) and register here.

JOIN HERE

Still have questions? Contact us here.