The first real entry-level jet

The Citation 500 was hardly a rose, but by any other name it may have jumpstarted the corporate jet age more than any other airplane.

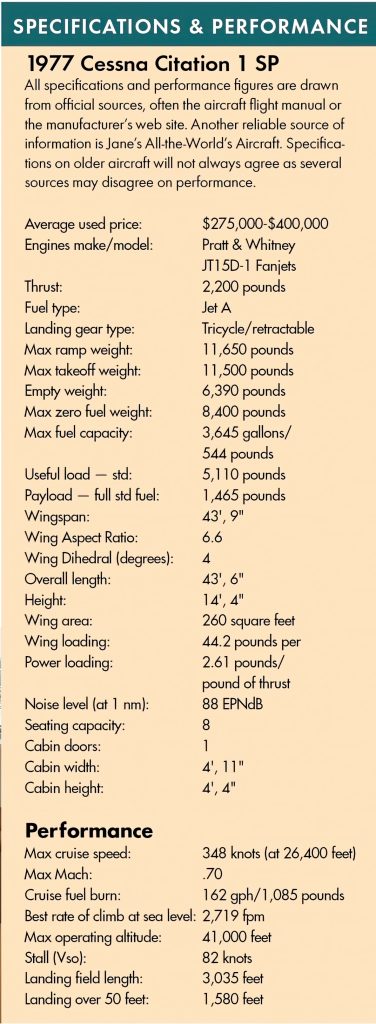

By today’s standards, the first Citation (originally named the Fanjet 500 and later rebranded as the Citation 1 and finally the Citation 500) was perhaps the ultimate entry-level business jet. In 1972, it was one of the first corporate jets to be authorized for single pilot operation and the first in what was to become the world’s most popular line of business jets. Cessna’s 500 series Citations brought on-demand jet travel to folks who otherwise would have been relegated to the airline’s timeline.

For people with the means and the need to travel on their schedule rather than an arbitrary timeline, who always want to fly first class, want to take along several passengers at nearly the same price, and want to define most other flight parameters, a Citation was a dream machine.

The follow-on Citation 1 SP could be flown with a crew of one, making the airplane a leader in the trend toward owner/pilot operation. That was the market Cessna hoped to dominate, and the model 1 SP was just the airplane to do it. Reasonably competent pilots with commercial/multi/instrument ratings discovered the Citation was a surprisingly quick teacher. Systems weren’t that complex, and if the price of admission was steep, there was a definite feeling of pride in saying to a client of friend, “I’ll pick you up in my jet.”

Within a year or two of its introduction, the first Citation was certified for flight at FL410, and a single pilot up front left room for seven passengers.

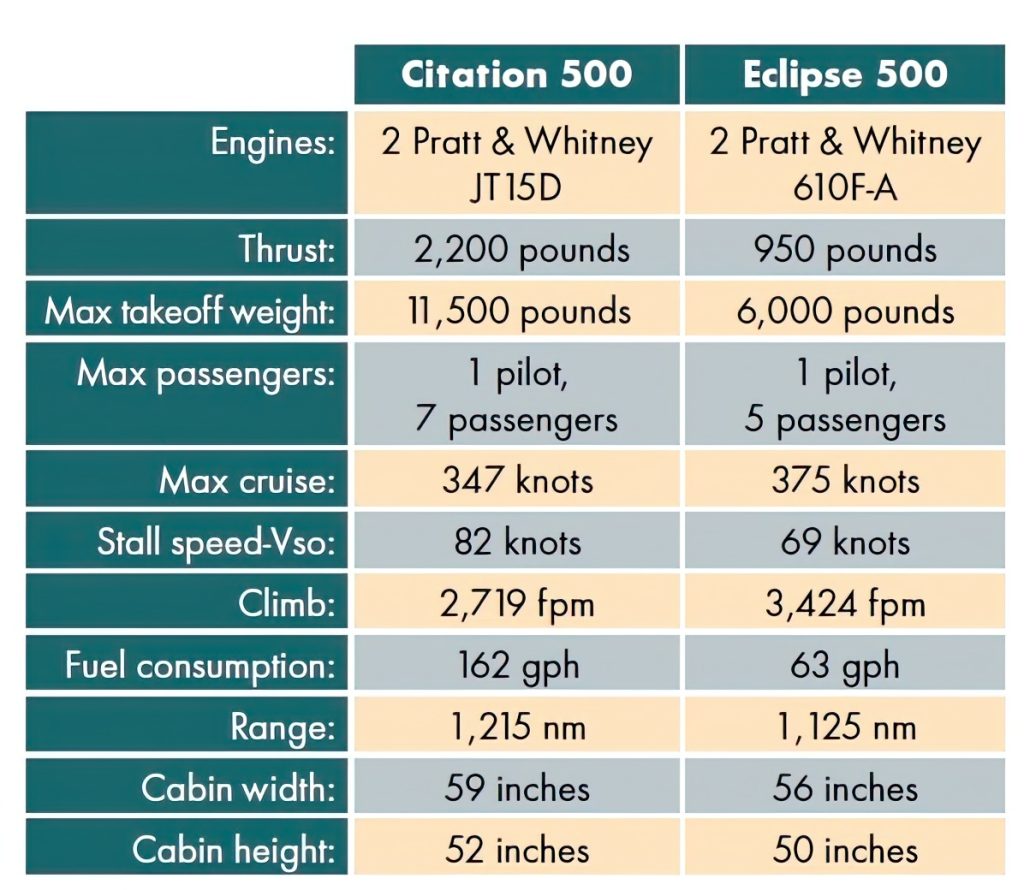

Perhaps more significantly, the Citation was introduced in 1973 at a price ($695,000) close to what Eclipse CEO Vern Raeburn hoped to charge for his first Eclipse 500s 35 years later.

Pretty obviously, 1973 dollars would be worth far more than 2020 dollars (today it would be about $4 million), but even so, Cessna sold some 350 of the first Citations. Raeburn never realized his dream of turning out 1,000 airplanes a year, but he did sell 260 partially completed Eclipse 500s before the company went bankrupt. (Most Eclipse buyers needed to spend at least another $100,000 to bring their airplanes to operational status, a successful process the new company called the Total Eclipse.)

Today, you can buy an original Citation 500 in decent running condition for as little as $200,000 and a 1 SP goes for only $350,000. For those pilots looking to join the jet set at an entry-level price, you can’t do much better than that.

It’s true the purchase price on an older, first-generation used jet can be little more than the price of admission considering that jet operating costs and maintenance expense can be staggering — all the more so on an airplane produced in the early ’70s. Still, for those willing to shop carefully and have a comprehensive pre-purchase inspection performed on a candidate jet, an early Citation may be a worthwhile initial investment in a pure turbine.

Be aware, however, that a used, early Citation is liable to be very well-used. People rarely buy aircraft in this class to let them sit on the ramp. Many owners average 250-300 hours a year of flight time, so a pre-owned original Citation that’s been religiously maintained and flown by the book may have 8,000 hours or more on the airframe. If it’s been kept in good shape and the avionics have been progressively upgraded, that may not be a problem, but it’s a definite consideration when you’re shopping.

Also, remember that just because an early Citation is comparatively inexpensive, don’t mistake it for a jet version of the Skyhawk. It is perhaps one of the easiest corporate jets to fly with a level of complexity no worse than that of a 421 (in fact, the Citation is said to be far easier, safer, and more reliable than that of the Golden Eagle). Citation approach speeds rarely exceed 100 knots, and the level of systems complexity is far less than on Cessna’s top corporate piston twin. In fairness, however, the Citation is 11,500 pounds gross, which is several thousand pounds heavier than the Golden Eagle, and it may take a while to adjust to the control response of a heavier machine.

In other words, this is not a VLJ, whatever that is. No one has ever adequately defined a very light jet, though the market has made room for the type. At nearly 6 tons max gross, the original Citation may be a little large and heavy for the honor. Moving that much heft around the sky demanded significant power and, for that reason, the Citation sported Pratt & Whitney engines of 2,200 pounds thrust each. That’s more than twice the power of the Eclipse, and the fuel burn was appropriately more than double.

Today, the only true certified VLJ may be the aforementioned Eclipse, though it was recently joined in the class by the single-engine Cirrus Vision.

Coincidentally, the Citation 1 scores similar performance to the Eclipse in several areas. Here’s a look at the comparative numbers:

A recent analysis of Controller.com listed some 70 Citation 500s and 1 S/Ps for sale, so there’s a wide range of early model 500s to choose from. A few had even been upgraded to the Sierra Industries Williams FJ-44 Eagle II conversion that adds about 40 knots to cruise, improves climb, improves max operating altitude (to 43,000 feet), and reduces fuel burn. These were generally priced just over $1 million.

The majority of the other early Citations were ticketed at less than $500,000. Remember, these were asking prices not getting prices. You might very easily find you could buy one of these aircraft for the aforementioned $350,000.

If you needed to carry eight folks a short distance, a Citation 1 SP might be just the ticket.

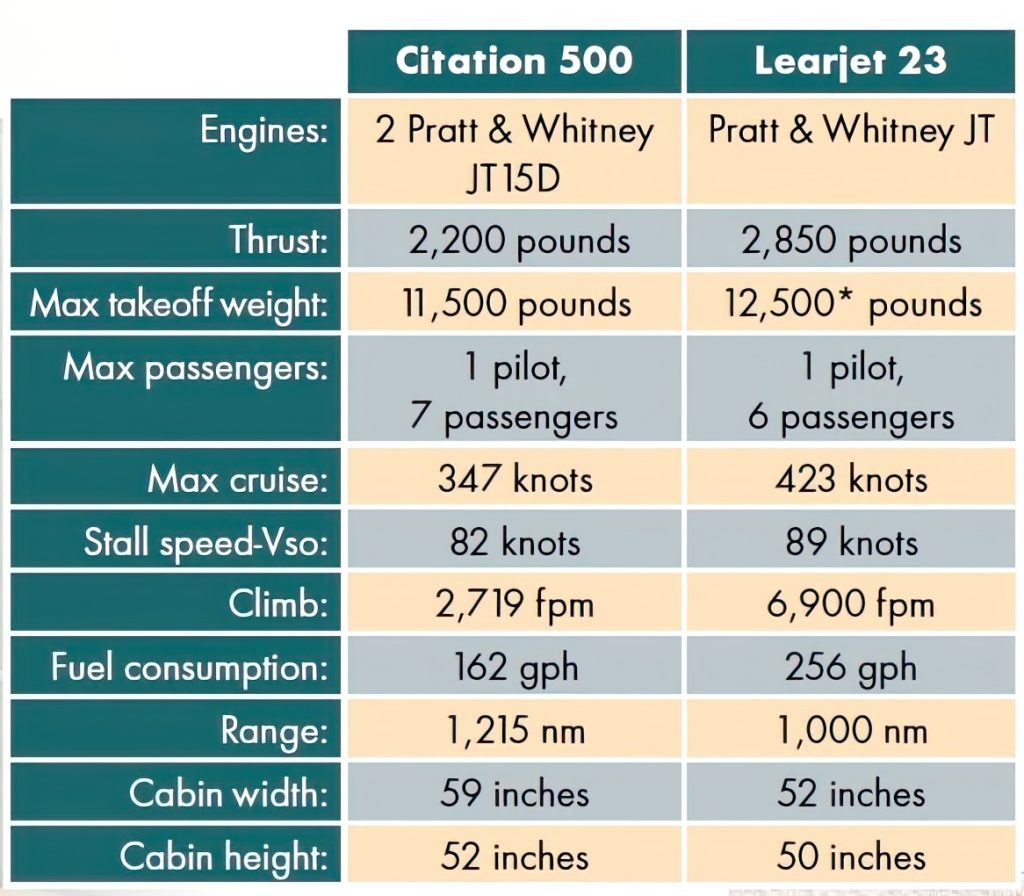

It’s also important to remember that some of the Eclipse numbers may have been more than a little imaginary. A more interesting and timely comparison might be with the Learjet 23.

Here’s a brief comparison of Learjet vs. Citation 500 performance and specs.

Generally speaking, the Learjet 23 was a rocket in performance. A good friend who flew F-86 Sabre jets during the Korean War and went on to fly corporate aircraft for a living said the Lear 23 could easily beat the Sabre to 41,000 feet.

There was a price to be paid for such performance, however. Fuel burn was about 50%-60% more in the Learjet 23 than in a Citation 500.

Just as some aspiring pilots sometimes buy older piston aircraft specifically to earn their private or instrument tickets, another practical benefit of a Citation 1 SP might be to earn your type rating. Early Citations are popular in the training regimen because of their relatively low initial cost and modest operating expense. Once you’re legal to fly the Citation, you might be surprised at the time you can save over airline travel on trips of 500-800 nm.

Perhaps coincidentally, the newer Cessna Mustang model 510 has performance numbers nearly identical to those of the Citation 1 SP. It’s also a more compact and lighter jet. On the downside, the 510 is fitted with six rather than eight seats.

For those with only $350,000 to spend, however, the Citation 1 SP is perhaps the only airplane that allows you to join the jet set.