By Kevin Stevens

As a previous owner of three planes — a Piper Turbo Arrow III (N6399C), a Piper Dakota (N8163E), and a Cessna 310Q (N69797) — I’ve enjoyed buying, restoring, and upgrading these aircraft, only to sell them as offers came unsolicited. As my father used to say, “If the price is right, sell.”

All my planes had low-time airframes, and I’ll bet that, with just one owner, the 1974 C310Q was by far the cleanest in the U.S. I got it with 2,100 total time (TT), and we knew the original owner here in Arizona. After my oldest daughter got a few hundred hours of multi-time in the 310 and began her airline career, we decided to sell it to a pilot in Colorado, who I believe has since upgraded the avionics.

Finding a Diamond in the Rough

That left us without a plane for about six months. Then a wonderful broker and friend, John Calhoun of Fresh Aircraft Sales, found us a 1980 T182 powered by a turbo-normalized Lycoming O-540. It had been a Civil Air Patrol (CAP) plane based in the Northwest. Something had happened to its turbocharger, and CAP decided to sell it rather than replace the turbo. Fortunately, I was at the right place at the right time to work out a deal to purchase the plane. I bought it, sight unseen, knowing up front that it needed a brand-new turbo. Working with CAP and a local A&P/IA who I know, we settled on a price I felt was fair.

We had to buy a new turbo for $3,000 and install it there in Idaho, as the plane couldn’t be flown without a functioning turbo. Before we could fly the plane, though, we discovered we would also have to get in compliance with the wing strut AD on the right-side strut. That was costly, as parts and labor were pushing $9,000. While the strut AD was being completed, we replaced the seat tracks as well, since the carpet was already out.

While two A&P/IAs (a local one and my friend from Arizona who was overseeing the project) were working on the plane in Idaho, a few local flight schools and a couple of local pilots at the airport asked if I was willing to sell it. They were all very interested in the plane because CAP maintains excellent logbooks and has a great track record with their aircraft. The local guys even knew some of the CAP pilots who flew it in the Northwest. A T182 with a turbo-normalized Lycoming is a desirable plane in the mountains. It’s a rare find, I’m told.

Twice I was offered quite a bit more than I had already invested in it, but I decided against parting with it. And I still hadn’t even seen the plane in person. I knew I couldn’t replace it for what I’d paid and was going to have into it when completed. I looked at prices of low-time T182s and I was way ahead of anything out there for sale.

The Interior Restoration and Avionics Upgrade

Once the turbo and wing spar AD work was finished, we flew the plane to a shop at KPRC (Prescott Regional Airport) in Arizona for interior work. Powell Aircraft Interiors completely removed the original disco-era red interior. They also took out the windshield to provide access behind the panel and to re-cover the dash. They worked closely with Zulu Avionics to remove the old vacuum system and replace it with a powder-coated metal panel featuring a Garmin G500, two G275s, GTX 345, PMA 7000, GTN 625, and JPI 930.

The GTN 625, PMA 7000, and GTX 345 were already in the plane when I got it, and I also decided to keep the KX-155As, T&B, airspeed, VS, and altimeter as well. I’ve been flying these old round dials since the 1970s, and after a few conversations with Jorge at Zulu, we decided that even though I didn’t legally need them, I would keep them because I like the legacy instruments. My old eyes follow them easily, along with the new G275 displays.

We went with the G275s over the G5s I had originally liked because there were some issues with the KX-155As and the G5s reading each other. To correct that issue, I would have had to replace two nav/comms. It was better just to upgrade to the G275s, and it cost less as well. We added a JPI 930 for engine monitoring and to remove all the old gauges. Not only did it clean up the panel, the JPI 930 is amazingly accurate. Fuel and temperatures are easily read and controlled.

Eagle Air in KPRC removed and replaced the windshield with precision. I was already a very satisfied customer of theirs when I had my Turbo Arrow III two-piece window replaced with a one-piece a few years ago. Philip and his crew are the best. Their shop is second to none, and they worked alongside Powell’s and Zulu to complete the plane.

I moved the radio stack around to what I wanted for safety and ease of use. I put the G500 autopilot on top, as I had in the airlines, with the GTN 625 right below it. The comm panel went below that, and the comm radios and the transponder were placed at the bottom.

When researching the G500, most configurations I saw with the G500 autopilot had it located where I have my transponder. I have spoken to quite a few pilots who have accidentally bumped buttons on the G500 while adjusting prop, mixture, or throttle. Having the G500 up and away from that area is safer and it’s quicker, too, as it allows you to load the GTN and execute the function with less movement.

The project took more than six months to complete due to Garmin having delays with servo delivery, but we made the most of the time. With the interior completely out of the plane, it was easier for avionics and wiring installation. We also replaced the rubber fuel line connectors in the upper area where they come from wing into cabin. I believe there were two to four of these. You wouldn’t ever replace them unless you were looking for them or had the interior removed like we did.

Powell’s replaced all the plastic in the interior, added new seat belts, rebuilt the built-in oxygen regulator, and inspected the air lines.

The Exterior Work: Paint and Pants

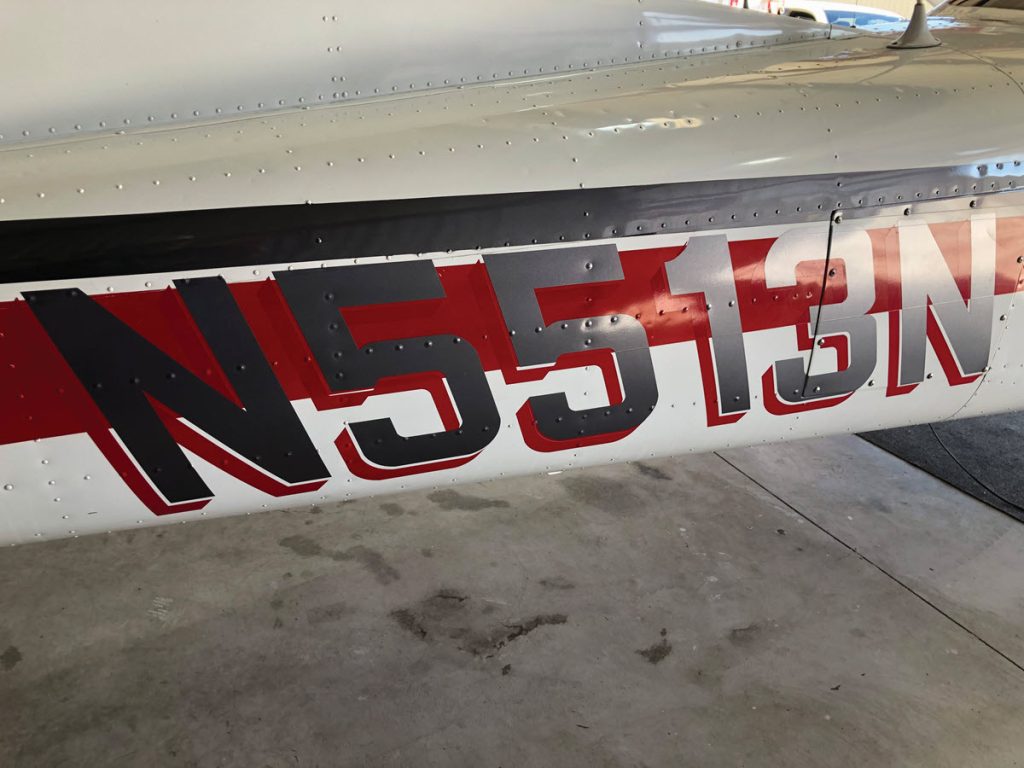

The plane’s exterior was a bit faded, but Chad from Johnson Detailing in Phoenix came out and repainted the faded black stripe to a beautiful metallic gray, matching the new N number gray as well as the interior gray. I found main wheel pants on eBay and had Chad put matching gray on them, too. I didn’t have a nose pant, but I’m not one who believes you gain anything significant with pants on or off. If you want a bit more speed, then push up the power.

Lessons Learned

I learned a lot from the project. For instance, the temperature probes need to be located on top of plane, not on the side, where airflow and exhaust might give the JPI bad readings. I also learned what you’re required to have for IFR if you remove the vacuum system, and the best location for radios and USB ports.

I’ve flown the plane quite a bit in high Colorado, Utah, California, New Mexico, and Arizona since completing the restoration and upgrade, and I love the turbo-normalized power. But I’m always open to moving on to a different plane if I find something I want and get the right offer for the one I have. Like Dad would say, “If the price is right, sell.”

TACKLING THE WING SPAR AIRWORTHINESS DIRECTIVE

I wasn’t even aware of the wing spar airworthiness directive (AD 2020-18-01) until we did the pre-buy and the CAP representative said the FAA had recently issued the AD because some 182s and 206s had cracks in a small area where the bottom of strut met the aircraft. A number of Cessnas across the country had developed cracks due to hard landings. As part of the pre-buy, we had an A&P/IA conduct an inspection. He found a crack about the thickness of a piece of paper that was about 1/16″ long. It was tiny but had to be fixed.

Cessna and another company make the repair kits that the FAA approved, but it was estimated to cost $3,000 to $7,000 just for the part. The labor for the installation would be additional. Fortunately, our wing spar wasn’t cracked through, but the area had to be repaired with a clamp that prevents separation. The problem is that it requires the plane’s flooring to be cut and removed to access the area, a time-consuming and expensive process. The FAA AD estimated the total cost of parts and labor to be $7,000 to $12,000. It was costly, but because of this plane’s value, it was definitely worth it.

Kevin Stevens started flying in 1976, earning all his ratings, private through ATP CFI/II/MEI. After college, he flew everything from Piper Navajos to Convair 580s. Then he flew for Continental Airlines as Captain on B727, 37, 57, 67, 77, 87, DC10, and A300, retiring after 37 years off 787 at LAX.